Keywordsearly school leaving education Europe 2020 strategy

JEL Classification I21

Full Article

1. Introduction

Early school leaving (ESL) is a topic of utmost importance at both European and national level, with significant social and economic implications. Young people who leave school can face a lack of jobs, social exclusion, poverty and health problems. The reasons for such a decision are complex, being a twinning of personal, social, economic, educational and family factors.

In the context of the effects of the 2007-2008 economic and financial crisis, coupled with a number of long-term challenges such as globalization, demographic decline and pressure on resource use, the European Council adopted on 17 June 2010, a 10-year program entitled the Europe 2020 strategy. This program aims to create the optimal conditions for each Member State of the European Union to develop and achieve a high level of employment, productivity and social cohesion. One of the objectives set in the Europe 2020 strategy in the field of education is to reduce the early school leaving rate below 10% in the EU and 11.3% in Romania.

In accordance with the European Union strategy, the Romanian Ministry of Education has formulated the Strategy for Reducing Early School Leaving in Romania (Ministry of Education, 2015). This national strategy was developed to ensure a coherent and coordinated approach on ESL, while achieving the ambitious goals of the national agenda and the Europe 2020 strategy. In the short term, the objective of the strategy was to implement an effective system of policies and measures for prevention, intervention and compensation to address the major causes of early school leaving, with a focus on young people in the 11-17 age group. The medium-term objective was to reduce to a maximum of 11.3% by 2020 the rate of young people aged 18-24 who have completed at most the lower secondary education cycle and who are not enrolled in any form of education. In the long run, the strategy aims to contribute to the intelligent and inclusive growth of Romania, by reducing the number of people at risk of unemployment, poverty and social exclusion (Ministry of Education, 2015).

In this article I want to answer the following questions: How is ESL defined in Romania? What are the factors that impact it? What are the main groups at risk of early school leaving in Romania? How has the ESL rate evolved in Romania in the last 10 years and what should the government do to prevent and reduce this phenomenon?

2. Early School Leaving Causes and Consequences

An early school leaver is a person who decides to leave an educational path early, before obtaining a diploma. Early school leaving (ESL) is defined in the European Union as the percentage of young people aged 18-24 who had completed at most a lower secondary education (the equivalent of the eighth grade) and were not in further education or training (Eurostat, 2020f).

Early school leaving is both an individual and a social problem. There are many personal, social, economic, educational and family reasons why young people leave school earlier, reasons that can be summarized in the following three theories:

- Psychosocial theory according to which people who leave school differ from those who complete their studies by one or more psychosocial attributes or personality traits such as: motivation, intelligence, self-image, aggression. With leaving school, some of these character traits risk becoming more pronounced, young people can become even more demotivated, more insecure and on this background of frustration, more aggressive.

- The interaction theory according to which ESL is a consequence of the interaction between the individual characteristics and those of the educational environment, including colleagues, teachers, parents, etc. The traditionalist perspective that states that the entire responsibility for leaving school lies with the students is contradicted by the situations in which young people leave school due to the traumatic experiences of failure and frustration lived in school. Teachers have a moral responsibility to know the subjective world of the student, to understand their expectations and aspirations, because in the absence of this connection, they also bear guilt in producing and amplifying ESL.

- The theory of external constraint according to which ESL is not so much a product of poverty as a product of the pressure of environmental factors that the individual cannot control, such as health status or family and professional obligations. Health problems, whether anatomical-physiological or psycho-intellectual in nature, give rise to inferiority complexes and frustrations that can culminate in ESL. Young people in these situations need to be emotionally supported by the ones around them and helped to overcome their fears in order to successfully complete their studies (Neamtu, 2016).

Analysing the specificity of ESL in the Western Balkans, Jugovic and Doolan (2013) concluded that Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro, Serbia and Slovenia have the same risk factors for ESL as Romania, such as: low economic and cultural family background, ethnic minority and migration status, type of school enrolled and motivation and academic achievement (Jugovic and Doolan, 2013). Just like Western Balkan countries, Eastern Europe countries, such as Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia put a strong focus on school completion and early school leaving of Roma children (O’Hanlon, 2016).

The main factors that determine the early school leaving in Romania can be divided into two main categories, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Factors that determine the early school leaving in Romania

| Factors that influence the student / family regarding the demand for education | Factors that influence the education offer |

| Low income per family | Insufficient number of places and limited availability of programs aimed at reducing early school leaving |

| Low territorial accessibility of education services in remote rural areas | Insufficient infrastructure provided in schools |

| Involving children in seasonal work and caring for younger siblings | Insufficient support for young people belonging to minority groups |

| Migration of parents from some communities abroad | Poor quality of teaching and learning processes |

| The level of education of the parents, especially the level of education of the mother |

Insufficient involvement of teachers in the relationship with their students |

|

Parents' attitude towards the importance of education |

Lack of communication between different levels of the education system |

|

Children with disabilities and special educational needs |

Insufficient support for young people with disabilities |

|

Health, early marriage and / or pregnancy, other personal reasons |

Lack of financial resources at the level of the Ministry of Education for reducing early school leaving in Romania |

Source: Strategy to Reduce Early School Leaving in Romania (SRESLR) (Ministry of Education, 2015)

The main groups at risk of early school leaving in Romania are young people from low-income families, young people from rural communities, Roma and other minorities.

- Children and young people from poor families; In Romania, the learning outcomes of children from poor families are far behind the outcomes of the ones in wealthier families. Although in the last 10 years, Romania made significant progress in the fight against poverty, in 2019 it registered the second highest percentage of people at risk of poverty and social exclusion from European Union after Bulgaria, in proportion of 31.2%. At risk-of-poverty, Eurostat includes persons with an equivalised disposable income below the risk-of-poverty threshold, which is set at 60% of the national median equivalised disposable income (after social transfers) (Eurostat, 2020k). Also, young people aged 18-24 in Romania register a very high percentage of poverty risk of 38.5%, the second in the EU after Greece (Eurostat, 2020a). In Romania, poverty is concentrated in two main regions Southwest Oltenia and the Northeast (National Institute of Statistics, 2019), so the government should adopt customized solutions for each region.

- Children and young people from rural areas; In 2018 in Romania the rural population represented 46.1% of the total population (National Institute of Statistics, 2020), significantly higher than the EU`s average of 29.1% (Eurostat, 2020i). Moreover, people in the countryside are confronted with the second highest risk of poverty or social exclusion in European Union and have the worst housing conditions. (Eurostat, 2020b). They live in overcrowded households, and the housings lack at least one of a number of basic facilities such as daylight, a bath/shower or a toilet, or a proper roof (Eurostat, 2020j). In these circumstances, it is explicable that in 2019, children and young people from rural areas in Romania record the second highest percentage of early leavers from education and training after Bulgaria, of 22.4%, more than double the EU average of 10.6% (Eurostat, 2020d). The educational performances of children in rural areas are lower than of those in urban areas and the ESL rate significantly higher. The government should continuously develop programs designed to reduce poverty in villages, and help children to have access to quality infrastructure and qualified teachers.

- Roma children and young people and other marginalized or underrepresented groups. In Romania, the Roma are an ethnic minority represented in the parliament since 1990. According to the 2011 census, Roma population was 621,573 people,3.09% of the total population, being the second largest ethnic minority in Romania after Hungarians (Romanian census, 2011). However, the unofficial number is much bigger as many Roma do not declare their ethnicity in the census and do not have an identity card or birth certificate. Many Roma still face severe poverty, profound social exclusion and discrimination but the lack of reliable statistics is an important obstacle to the correct estimation of the magnitude of these problems. Data show that the Roma population is affected to a much greater extent than the rest of the population by high early school leaving rate and high illiteracy levels (Publications Office of the European Union, 2014). Moreover, female Roma pupils face much higher risks of early school leaving than male, as their culture and family attitude prohibit the access to education and support early marriage. Due to these factors, employment rates continue to remain low for the Roma population. The Romanian government has developed National Roma Integration Strategy 2015-2020 (NRIS) for Roma integration which seeks to eliminate poverty and social exclusion through targeted education, employment, healthcare and housing policies. For children with special educational needs, the state should continue to allocate funds to provide the necessary resources, support services, tailored transport facilities, access to technologies and assistive devices and other types of specific programs.

The negative consequences of leaving school are felt both by the young people who make this decision and also by the economies of the countries affected by this phenomenon. ESL is closely linked to unemployment, social exclusion, poverty and health problems. Not completing studies may reduce young people's chances of getting a job, or can make them accept lower pay levels, because they leave the education system without having the skills and training require on the labour market. The reduction of incomes will lead to the increase of social tensions, representing a factor of lowering the living standard. Studies show that ESL is a risk factor for juvenile delinquency, drug use and adult crime (Fagan and Pabon, 1990). When they reach adulthood, the young people who leave school risk perpetuating the same behaviour among their children, which leads to a deepening of the phenomenon. Moreover, they are more likely to become dependent on state social and unemployment benefits, which will have negative implications for the economy.

3. The Regional and National Framework of Early School Leaving

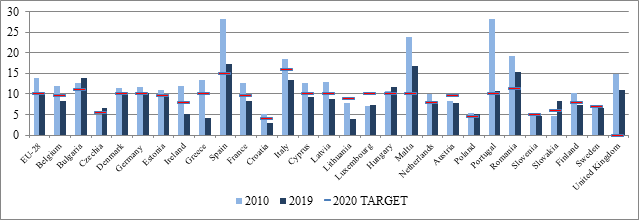

In the context of the economic and financial crisis of 2007-2008, the European Union developed the Europe 2020 strategy, with the general objective of economic recovery of the member countries by ensuring smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. In order to achieve this goal, one of the main targets was to reduce the rate of early school leavers, from 14.4% in 2009, to less than 10% by 2020. In this category are included people aged between 18 and 24, who are only graduates of lower secondary education or some form of lower education and who are no longer enrolled in the education or training system. Reducing early school leaving meets both the goal of "smart growth", improving levels of education and training, and the goal of "inclusive growth", by addressing one of the most important risk factors for unemployment, poverty and social exclusion (Official Journal of the European Union, 2011). As can be seen in Fig. 1, progress has been made, but not in all member states of the European Union equally.

Figure 1. Early leavers from education and training, 2010 and 2019 (% of population aged 18-24)

Source: Eurostat, 2020e

In 2019, out of a total of 28 EU member states, 16 countries registered a lower early school leaving rate than the national target, 11 countries, including Romania, failed to reach the level set in the Europe 2020 strategy, and the United Kingdom did not have drawn a national target. Romania was in second place in the European Union after Malta in terms of the difference between the ESL rate and the national target for 2020. Given the big gap, the chances for Romania to recover in 2020 the difference of 4 percentage points are minimal.

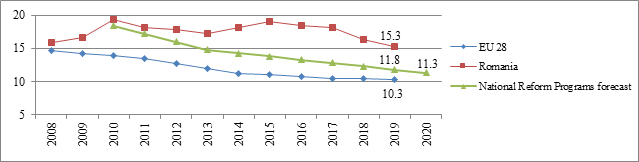

In the context of demographic decline that Romania is facing, caused by low birth rates, emigration and an ageing population, reducing early school leaving rate is a national key priority.Romania has translated at national level the objectives of the Europe 2020 strategy through the National Reform Programs (NRP), according to which the country`s target was to reduce the ESL rate below the level of 11.3% by 2020 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2011). This target was set at a level above the European target of 10%, but was based on a realistic assessment of the peculiarities of the Romanian economy. As can be seen in Fig. 2 between 2010-2019, Romania failed to follow the trajectory drawn within the NRP, registering on average a gap of 3.33 percentage points between the level achieved and the forecast one.

Figure 2.Early school leaving rate, EU target: <10%, Romania target: <11.3%

Source: Eurostat, 2020c, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2011

In most EU countries, young men have a higher ESL rate than young women, with the exception of the Czech Republic and Romania. Without the difference being too big, in 2019, in Romania the rate among women was 15.8%, and for men 14.9%. From the point of view of the labour force, in Romania the ESL rate among the young employed population is higher by 0.2% compared to the young population that does not have a job. Romania has the second highest percentage in the European Union (5.3%), after Bulgaria, among people who do not want to work and who have left school. Most of them are women, Romania registering the largest gender difference in the European Union, respectively by 6.9 percentage points more women than men (Eurostat, 2020c).

Regarding the area of origin, in 2019 in Romania the highest rate of ESL was registered in rural areas (22.4%), followed by smaller cities and suburbs (15.7%) and finally in large cities (4.3%). In most EU countries, the differences in ESL rates between these three environments are relatively small, but in Bulgaria and Romania they are significantly higher (Eurostat, 2020d). Analyzing the level of education, in each of the last 10 years, the ESL rate was higher in lower secondary level of education than in primary level of education. The level of these rates are all the more worrying as Romania is facing a significant decrease in the number of students enrolled in pre-university education. Between 2009-2018, the number decreased by 388,779 students (a 11.4% decrease), the largest drop being recorded in secondary school (-17%) and high school (-23.7%) (Ministry of Education, 2018).

In addition to the problems related to ESL, Romania`s performances in the PISA tests are also decreasing from an average score of 437.7 in 2015 (OECD, 2018) to 428 in 2018 (Schleicher, 2019). The proportion of 15 year-olds underachieving in reading was 40.8%, mathematics 46.5% and science 44%, thus Romania is positioning itself on the last places in the EU together with Bulgaria and Cyprus. According to the data, 4 out of 10 Romanian young people do not reach the basic level needed to effectively integrate into the knowledge society at the end of compulsory education (Ministry of Education and Research, 2019). Teachers have a very important role in preventing ESL and increasing the school performance of young people but in the rural area there is a serious shortage of qualified personnel. The government must give teachers a sense of well-being, intelectual fulfillment and satisfaction. According to the OECD’s Teaching and Learning International Survey, in 2018, only 41% of Romanian teachers believed that their profession is valued in society and only 23% declared that they are satisfied with the salary they receive for their work (OECD Publishing, 2020). When human dignity is affected, the degree of professional involvement risks being very low. The salary raises started in 2018 could be a solution to increase the degree of motivation and teaching performance.

4. Conclusions

Each case of ESL is particular, has its own motivation and requires a complex analysis. Early school leaving is considered a phenomenon because it is a complex process with extraordinary implications. Moreover, the determining factors multiply and diversify every year. Romania`s government should focus on the main groups at risk of early school leaving, respective: children and young people from poor families, from rural areas and from Roma families together with other marginalized or underrepresented groups. In order to reduce the ESL rate, the fight against poverty and social exclusion must continue to be a national priority in Romania. Roma people are at a much higher risk of poverty than the general population, so special attention must be paid to them. According to a 2014 World Bank study, 9 out of 10 Roma live in severe material deprivation, one-half of Roma children grow up in overcrowded housing, and one-third in slum dwellings. These improper living conditions increase the chances of suffering from early malnutrition or diseases that jeopardize healthy development in the crucial first years of life (World Bank, 2014). For them and for poor non-Roma families, the social assistance programs developed by the government are very important, such as: the allowance for family support, the “Corn and Milk” program, free school supplies for students, etc. In order to improve access to school and increase the chances of success at school for Roma children, the government should also supplement the number of Roma mediators that facilitate communication between teachers and Roma families. Families are responsible for meeting the basic, physical and social needs of children, for their social, emotional and cognitive development, thus contributing to the child's success in school and in life.

Reforms in education need time and continuous effort to produce effects along with strong coordination from all key actors. Romania`s government should act in three directions: prevention, intervention and compensation. The reality is that ESL has existed and exists in every society and cannot be eliminated, but prevention measures are essential in reducing the risk of leaving school before the first problems appear. The intervention measures aim at eliminating the incidence of ESL, by improving the quality of education and vocational training, by providing specific support to students or groups of students at risk, as a result of the early warning signals received. The compensation measures aim to support the reintegration into the education and training system of people who have left school prematurely and the acquisition of the necessary qualifications for access to the labour market.

Another factor that determines the early school leaving in Romania is the insufficient infrastructure provided in schools. In Romania, a large part of the funds for education are allocated for the salaries of teachers, school principals and auxiliary staff, so that the remaining resources for investments in educational infrastructure are limited. According to the Education and Training Monitor in 2019 conducted by the European Commission, in Romania the school network is lagging behind demographic trends and the need for modernization is high. The situation is much worse in rural areas, where is a great need to improve sanitary conditions and provide children with modern learning spaces (e.g. science laboratories, gym halls, libraries) (European Commission, 2019). Schools in the rural area are also less accessible as school transportation services are insufficient. Distance from school and lack of services transport are among the main reasons for ESL and absenteeism, especially for students from disadvantaged or minority groups. Differences in education infrastructure can lead to additional gaps regarding the quality of education between urban and rural schools. The poor infrastructure in schools also affects children with disabilities, as most educational institutions do not have access ramps and toilets for pupils with special needs.

The challenge of lowering the ESL rate is even greater in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, as face-to-face teaching is being replaced by online teaching. Although Romania recorded a rapid expansion in its proportion of households with internet access, with an increase of 30 percentage points between 2012 and 2019 (Eurostat, 2020h), in 2019, 18% of the population have never gone online. The largest share among those who have never used the internet is made up of elderly and people with low incomes (European Commission, 2020). Moreover, the divide between rural areas and urban area is particularly strong in Romania, both areas having a lower overall level of internet access than the EU-28 average. According to a study elaborated by Romanian Institute for Evaluation and Strategy in April 2020, the access of school children in Romania to online education is precarious. 32% of children enrolled in pre-university education do not have individual access to a dedicated functional device (e.g. laptop, tablet, desktop) for online school. Taking into account that in the 2019-2020 school year, 2,824,594 students were enrolled in pre-university education, the actual number of children who do not have access or have limited access to a device to participate in online education is 903,870. More than a quarter of these children`s parents stated that they would not spend money to purchase such equipment. Furthermore, of the children who have access to the Internet, 12% do not have a strong enough internet connection to be able to support the online courses (IRES 2020).

In order to modernize the educational infrastructure and to ensure access to distance learning activities for children, the government must allocate additional funding to the education sector. Public spending on education is very low in Romania, while the sector’s investment needs are high. In the last 7 years, Romania was in the last place in the EU in terms of public expenditure on education, with an average of 3% of GDP and in the last place in terms of the funds allocated for primary and preschool education (Eurostat, 2020g). Along with national funds, European funds must be used to modernize the schools infrastructure and digitize Romanian education. The European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) is the main vehicle through which the European Union supports investment in education infrastructure. €350 million has been earmarked in 2014-2020 under the ERDF to support investment in educational infrastructure in Romania, covering all levels from early childhood to university education infrastructure. Priority is being given to areas where enrolment rates in pre-school education are low and early school leaving is high. In general, funding is available for the modernization of existing infrastructure, the construction of new buildings and purchase of equipment. For the future, it is envisaged that the InvestEU Fund will provide an EU budgetary guarantee to leverage investment in school infrastructures that are green, digital and fit for the 21st century’s new teaching and learning methods (European Parliament, 2020).

In the context of an aging population, a more active and educated workforce is a necessity. Concern for the prevention and reduction of ESL must be a priority for the Romanian education system as this phenomenon has important social and economic implications. A high rate of school promotion would provide skilled young people with real employment potential which will contribute to the country`s development and growth. The infrastructure offered in schools, the involvement of teachers, the attitude of parents and the feedback provided by society on education, are all of the utmost importance for reducing the phenomenon of early school leaving.

References

- European Commission, 2019. Education and Training Monitor 2019. Romania. p. 5. [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/education/sites/education/files/document-library-docs/et-monitor-report-2019-romania_en.pdf [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- European Commission, 2020. Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI). Romania. p. 11. [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/scoreboard/romania [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- European Parliament, 2020. Parliamentary questions. Inadequate funding for education. [online] Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-9-2019-003724-ASW_EN.html [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Eurostat, 2020a. People at risk of poverty or social exclusion. Code: ilc_peps01 [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/t2020_50/default/table?lang=en [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Eurostat, 2020b. People at risk of poverty or social exclusion by degree of urbanization. Code: ilc_peps13 [online] Available at: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_peps13&lang=en [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Eurostat, 2020c. Early leavers from education and training by sex and labour status. Code: edat_lfse_14 [online] Available at: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=edat_lfse_14&lang=en [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Eurostat, 2020d. Early leavers from education and training by sex and degree of urbanization. Code: edat_lfse_30 [online] Available at: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=edat_lfse_30&lang=en [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Eurostat, 2020e. Early leavers from education and training by sex. Code: T2020_40 [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/t2020_40/default/table?lang=en [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Eurostat, 2020f. Early leavers from education and training. [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Early_leavers_from_education_and_training [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Eurostat, 2020g. General government expenditure by function (COFOG). Code: gov_10a_exp. [online] Available at: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=gov_10a_exp&lang=en [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Eurostat, 2020h. Households - level of internet access. Code: isoc_ci_in_h [online] Available at: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=isoc_ci_in_h&lang=en [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Eurostat, 2020i. Urban and rural living in the EU. [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/EDN-20200207-1 [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Eurostat, 2020j. Severe housing deprivation rate by degree of urbanisation - EU-SILC survey. Code: ilc_mdho06d [online] Available at: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_mdho06d&lang=en [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Eurostat, 2020k. People at risk of poverty or social exclusion by age and sex. Code: T2020_50 [online] Available at: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?lang=en&dataset=ilc_peps01 [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Fagan, J. and Pabon, E., 1990. Contributions of Delinquency and Substance Abuse to School Dropout Among Inner-City Youths. Youth and Society, 21(3), pp.306-354.

- Jugović, I. and Doolan K., 2013. Is There Anything Specific about Early School Leaving in Southeast Europe? A Review of Research and Policy. European Journal of Education, 48(3), pp.363-377. DOI: 10.1111/ejed.12041

- Ministry of Education, 2015. Strategy to Reduce Early School Leaving in Romania (SRESLR), pp. 5-7, 25, 47. [online] Available at: https://www.edu.ro/sites/default/files/fisiere%20articole/Strategia%20privind%20reducerea%20parasirii%20timpurii%20a%20scolii.pdf [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Ministry of Education, 2018. Report on the State of Pre-university Education in Romania 2018, p. 4. [online] Available at: https://www.edu.ro/sites/default/files/Raport%20privind%20starea%20%C3%AEnv%C4%83%C8%9B%C4%83m%C3%A2ntului%20preuniversitar%20din%20Rom%C3%A2nia_2017-2018_0.pdf [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2011. National Reform Program 2011-2013 - Romania, p. 110. [online] Available at: http://www.mae.ro/sites/default/files/file/Europa2021/PNR_2011_2013.pdf [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- National Institute of Statistics - Romania, 2019. Dimensions of Social Inclusion in Romania. p. 15, [online] Available at: https://insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/field/publicatii/dimensiuni_ale_incluziunii_sociale_in_romania_2018.pdf [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- National Institute of Statistics, 2020. Romania in Figures. p. 10, [online] Available at: https://insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/field/publicatii/romania_in_figures_2020.pdf [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Neamţu, G., 2016. Encyclopedia of Social Assistance. Buchares, Romania: Polirom Publishing House.

- O’Hanlon C., 2016. The European Struggle to Educate and Include Roma People: A Critique of Differences in Policy and Practice in Western and Eastern EU Countries. Social Inclusion, 4(1), pp.1-10. DOI: 10.17645/si.v4i1.363

- OECD, 2020. TALIS 2018 Results (Volume II) Teachers and School Leaders as Valued Professionals, p. 56. [online] Available at: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/talis-2018-results-volume-ii_19cf08df-en#page1 [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- OECD, 2018. PISA 2015 - Results in Focus, p. 5. [online] Available at: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisa-2015-results-in-focus.pdf [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Official Journal of the European Union, 2011. Council Recommendation of 28 June 2011 on Policies to reduce early school leaving, pp.1-3. [online] Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32011H0701(01)&from=HR

- Publications Office of the European Union, 2014. Education: The Situation of the Roma in 11 EU Member States, p. 12. [online] Available at: http://publications.europa.eu/resource/cellar/5db33bbf-e951-11e8-b690-01aa75ed71a1.0005.03/DOC_1 [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Romanian Census, 2011. Population by ethnicity 1930-2011. National Institute of Statistics. [online] Available at: http://www.recensamantromania.ro/noutati/volumul-ii-populatia-stabila-rezidenta-structura-etnica-si-confesionala/ [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Romanian Institute for Evaluation and Strategy (IRES), 2020. Access of School Children in Romania to Online Education. [online] Available at: https://ires.ro/articol/394/accesul-copiilor--colari-din-romania-la-educa%C8%9Bie-online-- [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Schleicher, A., 2019. PISA 2018: Insights and interpretations. Publisher: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), p.6. [online] Available at: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/PISA%202018%20Insights%20and%20Interpretations%20FINAL%20PDF.pdf [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- World Bank, 2014. Achieving Roma inclusion in Romania – What does it take, p.12. [online] Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/eca/romania/Summary%20Report%20RomanianAchievingRoma%20Inclusion%20EN.pdf [Accessed 11 May 2020].

Article Rights and License

© 2020 The Author. Published by Sprint Investify. ISSN 2359-7712. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.