Keywords

JEL Classification F02, F50, O57

Full Article

1. Introduction

The post-Cold War period marked the consolidation of a unipolar international system, primarily shaped by the economic, political, and military dominance of the United States and its key Western allies. Over the past two decades, however, this unipolar configuration has gradually eroded, giving way to a more fragmented and contested multipolar landscape. Within this emerging global order, the BRICS countries—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—have increasingly positioned themselves as alternative centers of influence, challenging the traditional institutional frameworks and normative paradigms established by Western powers.

In this context, BRICS has evolved from a loosely connected coalition of emerging markets into a more structured and institutionalized alliance, seeking to influence and reshape global governance. A significant milestone in this trajectory occurred in January 2024, when the group expanded its membership to include Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). This enlargement not only reflects the bloc’s expanding geopolitical weight but also underscores its appeal to a wider group of states seeking greater representation in a multipolar international system.

In contrast, the G7—comprising Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States—remains committed to upholding a liberal international order anchored in Western norms, democratic governance, and market-oriented economic principles. As both BRICS and the G7 continue to consolidate their influence, critical questions emerge regarding their respective capacities to lead, reform, or redefine the architecture of global governance.

This article aims to address a key question within contemporary international relations: Can BRICS surpass the G7 in economic terms? To explore this, the analysis begins with a review of the historical development and institutional dynamics of each group. It then undertakes a comparative assessment of their economic performance and potential. Finally, the article considers the internal and external challenges confronting BRICS and reflects on the broader implications of an evolving balance of global power.

2. Literature Review

The concept of BRIC was first introduced in 2001 by Jim O'Neill, then Chief Economist at Goldman Sachs, to characterize four major emerging market economies: Brazil, Russia, India, and China. In his analysis, O'Neill compared the real GDP growth of these countries with that of the G7, the group comprising the world’s most industrialized nations: Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. He concluded that, beginning in 2001–2002, the BRIC economies would outpace the G7 in terms of real GDP growth, with China projected to significantly increase its share of global GDP over the following decade (O'Neill, 2001). Through this analysis, O'Neill highlighted the substantial investment potential of the BRIC economies. Since its inception in 2001 as an informal grouping, this coalition of countries evolved into a formal intergovernmental organization by 2009. In 2010, the bloc expanded to include South Africa—its first African member—thereby transforming from BRIC to BRICS. Interest in the organization surged in 2024, following the accession of Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates. Additionally, many other nations have expressed strong interest in joining the group. Comprehending the role of BRICS is essential in the context of an increasingly multipolar global order. As noted by Andrew Cooper in 2016, a statement that remains highly pertinent today, the role of BRICS in contributing to the diffusion of authority within the global system of the 21st century should not be underestimated (Cooper, 2016).

Over the years, scholars have increasingly directed their attention toward this organization, examining its origins and the objectives underlying its formation. While some view BRICS as a challenge to the existing international order, others recognize its potential to alter the current global distribution of power (Petropoulos, 2013). Oliver Stuenkel, a leading scholar in international relations, aims to provide a comprehensive and authoritative account of the BRICS, both as a conceptual term and as an institutional entity. In doing so, he delineates the evolution of BRICS into three distinct phases. In the first phase (2001–2007), the term BRIC was coined by Jim O'Neill of Goldman Sachs to categorize four major emerging market economies—Brazil, Russia, India, and China—as a purely investment-oriented grouping. The second phase (2008–2012) witnessed the transformation of BRICS into a political platform, albeit one characterized by an informal structure. The year 2012 marked the onset of the third phase, defined by a growing institutionalization of the group, exemplified by the establishment of the New Development Bank (NDB), headquartered in Shanghai, and the creation of the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA). According to Stuenkel, this institutionalization process signifies a deliberate effort by BRICS members to offer viable alternatives to the financial institutions traditionally dominated by Western powers (Stuenkel, 2015). Despite the gradual pace of institutional development among BRICS countries, Ramachandra Byrappa emphasizes that, much like the saying “Rome was not built in a day,” the bloc has sufficient time to establish the necessary organizational framework to fulfill its ambition of contributing to a more equitable international system (Byrappa, 2017).

In his work The End of American World Order, Amitav Acharya argues that the era of global dominance by a single power—first experienced under Britain and later under the United States—has come to an end. He contends that BRICS will be sufficiently influential to prevent a re-emergence of unipolarity centered on the United States and will instead contribute to the emergence of a multiplex world order. Acharya defines this multiplex world as "a world of diversity and complexity, a decentered architecture of order management, featuring old and new powers, with a greater role for regional governance." While he does not consider the BRICS nations individually or collectively powerful enough to unilaterally dominate the global system, he asserts that they possess the capacity to reshape the mechanisms through which global order is managed (Acharya, 2020).

Scholars have examined the fundamental divergences among BRICS member states in terms of their political systems, economic capacities, military power, demographic profiles, and global aspirations—particularly within the sphere of international financial governance. In his 2006 analysis of the BRIC grouping, Andrew Hurrell underscored the profound heterogeneity among its members, notably describing China as being "in a league of its own" (Hurrell, 2006). Nearly two decades later, this disparity in economic development remains evident. Although BRICS professes a commitment to equal representation among its members, many economists contend that the organization is increasingly perceived as being shaped by, and aligned with, China’s strategic ambitions.

The divergence in economic development among BRICS members is not the sole source of internal tension; military rivalry between the bloc’s two most influential states—China and India—also poses a significant challenge. Persistent border disputes, coupled with India’s strategic military partnerships with countries such as the United States and Japan in response to China’s assertive behavior in contested maritime regions, represent a potential impediment to deeper cohesion and unity within the BRICS framework (Basrur, 2017). Immanuel Wallerstein expresses skepticism regarding the future viability and internal cohesion of BRICS, referring to it as “a Fable for Our Time.” The renowned social theorist and economist views BRICS as a grouping that, over time, has revealed its structural vulnerabilities and whose geopolitical ambitions remain uncertain and contested (Wallerstein, 2016). The overarching conclusion derived from such critiques is that, given the bloc’s significant internal disparities and challenges, achieving genuine unity, cohesion, and a shared geopolitical vision appears highly improbable.

3. Methodology

This article employs a qualitative comparative analysis complemented by quantitative indicators to evaluate the extent to which the BRICS coalition can rival or surpass the G7 in terms of global influence and institutional relevance. The research is grounded in an interdisciplinary framework, drawing from the fields of international relations, global political economy, and institutional analysis to provide a nuanced understanding of the dynamics between these two blocs.

The article employs a comparative analytical framework to evaluate the economic power and performance of the BRICS and G7 countries. It focuses on key economic indicators—including GDP growth rates, population size, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows, and merchandise exports—over the period from 2001 to 2023. Although the BRICS bloc expanded in January 2024 to include four additional members—Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates—this analysis focuses exclusively on the original five founding members: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. This narrower focus allows for a more coherent and longitudinal examination of the group's economic evolution and geopolitical impact over time. The analysis is grounded in empirical data sourced from authoritative international organizations, including the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

The data used in this study are derived from a combination of primary and secondary sources. These include official documentation such as BRICS and G7 summit declarations and treaties, as well as scholarly analyses by prominent authors including Oliver Stuenkel, Andrew Cooper, Amitav Acharya, and Immanuel Wallerstein. Additional data are drawn from international statistical databases and reports published by global institutions and policy research centers.

While this comparative analysis aims to offer a comprehensive evaluation, the study acknowledges several limitations. Chief among these is the challenge of quantifying geopolitical influence and institutional legitimacy, which often involve subjective assessments. Moreover, as both BRICS and the G7 are subject to ongoing political and economic transformations, the findings of this study should be interpreted as reflective of current trends and dynamics, rather than definitive or static conclusions.

4. The Evolution of BRICS and G7

The acronym BRIC was first coined by economist Jim O'Neill in 2001 to refer to the large emerging economies of Brazil, Russia, India, and China, which were expected to become major drivers of global economic growth. BRICS (BRIC countries and South Africa) was formally established in the aftermath of the 2009 financial crisis, reflecting the growing economic and political influence of its members, as well as their perception that the interests of both themselves and other developing nations were underrepresented in the international political arena. As members of the G20—a forum established to address pressing global economic and political issues—the five BRICS countries recognized the value of forming a more cohesive and compact grouping to better advance their shared interests. Cooper and Stolte examine the dualistic strategy adopted by BRICS states, which enables them to function concurrently as both institutional 'insiders' and 'outsiders' within the G20 framework. Their analysis explores the nuanced and seemingly paradoxical nature of this international posture, arguing that the BRICS nations deliberately employ this dual strategy to balance engagement with established global governance structures while simultaneously promoting alternative narratives and reforms that reflect their own developmental priorities and geopolitical aspirations (Cooper and Stolte, 2019).

An important milestone in the institutional evolution of BRICS was reached in 2014 with the creation of the New Development Bank (NDB), also referred to as the BRICS Development Bank. The NDB was established with the objective of financing infrastructure and sustainable development projects in BRICS nations and other developing economies (BRICS, 2014a). Its formation signified a shift from an informal consultative platform to a more formalized and institutionalized mechanism for cooperation. In the same year, BRICS also launched the Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA)—a $100 billion financial safety net aimed at providing liquidity support and precautionary instruments in response to short-term balance of payments pressures (BRICS, 2014b).

These institutional innovations not only reinforce intra-BRICS financial cooperation but also signal the bloc’s strategic intent to challenge the dominance of Western-centric financial architecture. Both the NDB and CRA are positioned as alternatives to the Bretton Woods institutions, particularly the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The governance structures of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have faced sustained criticism for disproportionately favoring developed nations—especially the United States—and for promoting policy prescriptions that have, at times, adversely affected developing countries. In response, BRICS aims to promote a more multipolar model of global economic governance, better aligned with the needs and priorities of emerging and developing economies.

The Group of Seven (G7) was established well before the formation of BRICS, emerging in the mid-1970s in response to the global economic instability triggered by the oil crisis. Initially composed of six leading industrialized nations—the United States, Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy—the group expanded in 1976 with the inclusion of Canada, becoming the G7. In 1998, Russia joined the group, resulting in the creation of the G8. This configuration remained in place until 2014, when Russia was suspended following its annexation of Crimea, reverting the group back to its current G7 format (European Commission, 2014).

The G7 was conceived as an informal platform for advanced economies to coordinate their economic strategies, address financial crises, and contribute to global economic and political stability. While its initial mandate centered on economic cooperation, the scope of the G7’s agenda has progressively broadened to encompass a wide array of global issues, including security, climate change, and public health. In its recent official statements, the G7 reaffirms its strong belief in democratic principles and free societies, universal human rights, social progress, and respect for multilateralism and the rule of law. Moreover, the G7 pledges to promote opportunity, shared prosperity, and the strengthening of international norms for the collective good. Its actions are anchored in respect for the United Nations Charter, the maintenance of global peace and security, and the preservation of a free and open rules-based international system (European Council, 2024). Despite Jim O’Neill’s early proposal in 2001 suggesting that representatives from the BRIC countries be incorporated to reflect changing global dynamics, the G7 has retained its exclusive character, continuing to exclude emerging powers from its institutional framework.

The primary distinction between the BRICS and G7 lies in their composition. The G7 consists of seven of the world's most advanced and industrialized economies, whereas BRICS brings together five major emerging economies that are significantly more diverse in terms of economic development levels and political systems. While G7 countries are generally perceived as proponents of Western values and interests, often supporting policies that sustain the current global economic order, BRICS positions itself as an alternative to Western-dominated governance structures. The BRICS coalition advocates for a multipolar international system, emphasizing principles such as state sovereignty, non-interference in domestic affairs, and the enhanced representation of emerging economies in global decision-making processes.

5. Comparative Economic Power between BRICS and G7

Despite being classified as emerging economies, the BRICS countries are distinguished by rapid economic growth, large populations, significant foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows, and important player in merchandise exports.

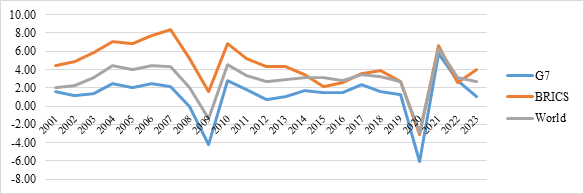

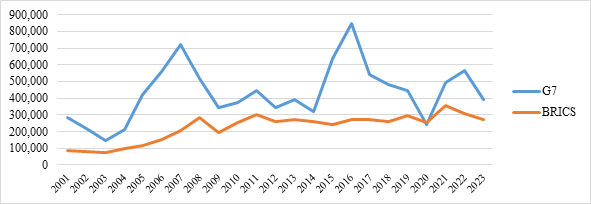

Jim O'Neill was initially drawn to Brazil, Russia, India, and China in 2001 due to their impressive GDP growth trajectories. When comparing GDP growth rates between BRICS and G7 nations over a 23-year period, the BRICS countries consistently outperformed, with an average growth rate approximately 3 percentage points higher than that of the G7. The sole exception was in 2022, when the G7 recorded higher economic growth—a result largely attributed to the contraction of real GDP in Russia. Figure 1 reflects the dynamism of emerging markets in contrast to the more mature economies of the developed world.

Figure 1. Average GDP growth (annual %): World, BRICS countries and G7 countries (2001-2023)

Source: World Bank Data, 2024a

If we examine the real GDP growth trajectories of BRICS member states over the past 23 years (Table 1), it becomes evident that the internal rankings have shifted. China, which had previously been the primary driver of growth in the group—and in which Jim O'Neill placed significant confidence when coining the BRIC acronym—has now been surpassed by India in terms of growth rate. India's economic expansion is underpinned by a favorable demographic structure, robust domestic consumption, and a series of market-oriented reforms that have fostered an investor-friendly environment. In contrast, China faces a range of structural and geopolitical challenges that have moderated its growth momentum. Nonetheless, both China and India continue to serve as the principal engines of growth within BRICS. Meanwhile, Brazil, Russia, and South Africa have experienced comparatively weaker performance, constrained by a combination of economic volatility and political instability.

Table 1. GDP growth (annual %) in BRICS countries (2001, 2010 and 2023)

| Country | 2001 | 2010 | 2023 |

| Brazil | 1.39 | 7.53 | 2.91 |

| Russian Federation | 5.10 | 4.50 | 3.60 |

| India | 4.82 | 8.50 | 7.58 |

| China | 8.34 | 10.64 | 5.20 |

| South Africa | 2.70* | 3.04 | 0.60 |

* Not yet part of BRICS Source: World Bank Data, 2024a

According to projections by the International Monetary Fund, over the next six years, the real GDP growth rate of BRICS countries is expected to be more than twice that of the G7 economies (IMF DataMapper, 2024). This anticipated growth differential enhances the appeal of BRICS nations as attractive destinations for foreign direct investment (FDI), particularly for investors seeking higher returns in emerging markets.

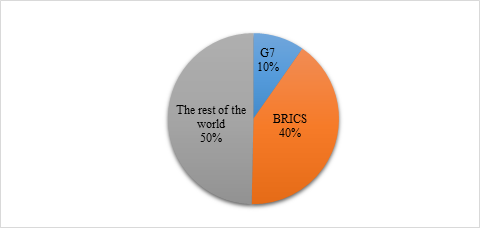

In addition to their rapid economic growth, the BRICS countries share another key characteristic: their substantial population size. As of 2023, the BRICS nations collectively account for approximately 40.6% of the global population, in stark contrast to the G7 countries, which represent only 9.71% (Figure 2). Although the BRICS’ share of the global population has experienced a slight decline over the past 23 years, the group continues to represent a major demographic bloc on the global stage.

Figure 2.The share of BRICS and G7 in the total population in 2023

Source: World Bank Data, 2024b

In terms of population, India surpassed China at the end of 2023, reaching an impressive 1.428 billion people, thereby securing the position as the most populous country in the world. China closely follows with a population of 1.411 billion (World Bank Data, 2024b). A large population can serve as a significant advantage for BRICS countries, providing economic, political, and social benefits. A sizable population creates a substantial domestic market for goods and services, thereby stimulating economic activity and attracting foreign investment. Nations like India, and to a lesser extent, South Africa, benefit from relatively young populations, which contribute to a growing labor force. A youthful and educated workforce can enhance productivity, savings, and long-term economic growth.

Furthermore, countries with large populations often wield greater political influence on the global stage, particularly in international organizations where population size can impact voting power, such as the United Nations. Additionally, a larger population can sustain a more substantial and capable military, bolstering a nation's defense capabilities and enhancing its geopolitical influence. As of 2023, China and India rank first and second globally in terms of active military personnel, underscoring the strategic importance of their population sizes (Ranking Royals, 2024).

Due to their large populations, over the years, BRICS countries have emerged as key destinations for foreign direct investment (FDI), as multinational corporations have sought to capitalize on the expanding consumer markets within these economies. In particular, China and India have benefited from the availability of a vast and relatively low-cost labor force, which has been a major draw for foreign investors. Meanwhile, Brazil, Russia, and South Africa have attracted FDI primarily through their rich endowments of natural resources. Over time, the BRICS nations have also implemented a range of economic reforms and invested in infrastructure development, further enhancing their appeal to international investors.

Figure 3.FDI inflows (million $): BRICS countries and G7 countries (2001-2023)

Source: UNCTAD, 2024

Figure 3 illustrates that over the past 23 years, FDI inflows into BRICS countries have demonstrated a generally sustained upward trajectory, with the exception of a notable decline in 2020, corresponding to the global economic disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, in the year of the pandemic, BRICS countries managed to attract more FDI than the G7 group due to a combination of structural advantages, policy responses, and sectoral dynamics that worked in favor of the BRICS bloc during that year. China, in particular, played a significant role in this trend. It became the world's largest FDI recipient in 2020, overtaking the United States, due to its effective pandemic control measures and rapid economic recovery. India also saw a 26,7% increase in FDI, driven by investments in the digital sector (Table 2).

Table 2. FDI inflows in BRICS countries (million $), 2019–2020

| Country | 2019 | 2020 |

| Brazil | 65,386.3 | 28,322.3 |

| Russian Federation | 32,075.6 | 10,409.9 |

| India | 50,558.3 | 64,072.2 |

| China | 141,224.6 | 149,342.3 |

| South Africa | 5,125.0 | 3,062.3 |

| TOTAL | 294,369.9 | 255,208.9 |

Source: UNCTAD, 2024

Eventhough FDI inflows into G7 countries have consistently remained at significantly higher levels in the rest of the years, their share at the global level has decreased. In 2001, FDI inflows into G7 countries represented 37.1% of global FDI, while BRICS countries accounted for just 10.9%. By 2023, FDI inflows into G7 countries had decreased to 29.3%, whereas BRICS countries' share had risen to 20.3%, with China maintaining its position as the leading recipient of FDI within the bloc and the 2nd in the world after the US (UNCTAD, 2024).

Although the BRICS countries exhibit substantial long-term potential for foreign direct investment (FDI)—underpinned by their large populations and expanding domestic markets—they continue to face notable constraints. These include political instability, inconsistent regulatory frameworks, and, in certain cases, the impact of international sanctions. In response, BRICS nations are undertaking a range of strategic measures aimed at enhancing their investment attractiveness. These efforts include improving regulatory clarity, upgrading infrastructure, diversifying economic structures, and promoting investment in high-growth sectors such as technology and renewable energy. The success of these initiatives, however, will largely depend on each country’s capacity to address persistent challenges, particularly those related to governance, policy coherence, and the implementation of meaningful economic reforms.

A key characteristic of the BRICS countries is their increasing significance in global merchandise exports. These five economies have emerged as prominent players in international trade, supported by their rich natural resources, expanding domestic markets, and increasingly diversified manufacturing sectors. Together, BRICS nations make a considerable contribution to global export volumes, with a crucial role in both the trade of raw materials and the export of value-added manufactured goods.

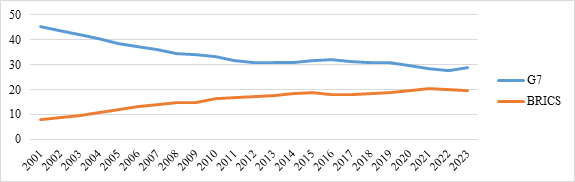

According to data from the World Bank, the G7 countries continue to lead in absolute terms in merchandise exports, owing to the size and maturity of their economies, advanced industrial capabilities, and long-established trade networks. However, BRICS countries, especially China, are progressively narrowing the gap, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.Percentage of worldwide merchandise exports: BRICS countries and G7 countries (2001-2023)

Source: World Bank Data, 2024c

In 2023 BRICS countries accounted for 19.6% of total global merchandise exports, highlighting their expanding role in international trade and their increasing competitiveness across both raw materials and manufactured goods. This percentage has more than doubled in the last 23 years, challenging the historical dominance of advanced economies in global trade.

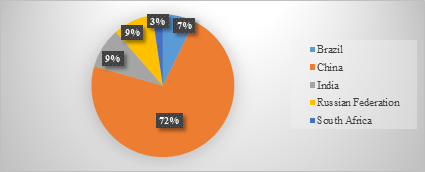

Figure 5.Share of merchandise exports by individual BRICS countries in 2023

Source: World Bank Data, 2024c

As it can be seen in Figure 5, China stands as the undisputed leader, not only within BRICS but also globally, with its dominance in the export of electronics, machinery, vehicles, and textiles. Its advanced manufacturing capabilities and strategic initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) have significantly strengthened its export performance. India, while traditionally recognized for its service sector, has emerged as a growing exporter of goods, particularly in pharmaceuticals, textiles, automobile components, and engineering products—driven by expanding manufacturing capacities. Brazil contributes substantially through its vast reserves of natural resources, ranking among the world's top exporters of agricultural commodities like soybeans, coffee, and meat, as well as iron ore. Russia plays a central role in the global energy market, exporting large quantities of oil, gas, metals, and fertilizers, and remains a crucial supplier despite the impact of international sanctions. Lastly, South Africa is a major exporter of precious metals, minerals, and increasingly, automotive products. Its mineral wealth underpins its status as a key player in global raw materials trade, while its industrial diversification efforts are gradually enhancing its export profile.

The growing economic clout of BRICS countries is reshaping global trade flows. While they continue to export primarily raw materials and commodities, there has been a marked shift towards more manufactured goods and high-tech exports as BRICS nations diversify their economies. The continued industrialization of countries like India and Brazil, coupled with China's dominance in global manufacturing, highlights the bloc's growing importance as a global exporter.

6. BRICS challenges

While the BRICS countries have recorded remarkable performances in terms of economic growth, population size, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows, and merchandise exports, they also face several challenges that may hinder their continued growth and success.

Political instability and governance challenges remain significant obstacles for several BRICS countries. Internal political volatility, particularly in nations such as Brazil and South Africa, often disrupts policy continuity and weakens investor confidence, making long-term economic planning and foreign investment more difficult. Additionally, persistent issues related to corruption and weak institutional frameworks undermine the effectiveness of economic reforms and policy implementation. According to the 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) published by Transparency International, all BRICS countries scored below the global average, suggesting that their public sectors are perceived as more corrupt than the international standard (Transparency International, 2023). These governance deficiencies can erode public trust, hinder administrative efficiency, and ultimately constrain the broader development potential of the BRICS economies. In comparison, G7 countries have consistently recorded higher scores than BRICS nations on the Corruption Perceptions Index, indicating stronger governance systems and a higher degree of institutional transparency and accountability.

Another vulnerability is the fact that the BRICS countries exhibit significant disparities in economic growth. As we have seen in Table 1, while China and India have experienced robust growth, Russia, Brazil and South Africa have faced periods of stagnation or recession (World Bank Data, 2024a). Additionally, structural economic imbalances, such as Brazil and Russia’s heavy reliance on natural resources, make these economies particularly susceptible to fluctuations in global commodity prices, which can further hinder their growth prospects. The significant disparities in political systems, economic structures, and geopolitical orientations among BRICS member states are often cited as indicators of the grouping’s inherent fragility. These divergences can challenge the bloc’s internal coherence and complicate efforts to formulate unified positions on key international issues.

It is also important to note that two of the five BRICS countries are facing significant geopolitical tensions, which have far-reaching economic consequences both for the individual countries and for the group as a whole. Russia has been subjected to a range of sanctions, particularly following its annexation of Crimea in 2014 and its military actions in Ukraine since 2022. Meanwhile, China has been engaged in an escalating trade war with the United States, which began in 2018 and has had considerable economic impact. The geopolitical tensions also expose the BRICS bloc to external pressures, particularly from the West, leading to greater fragmentation. The differences in foreign policy and economic strategies among the member states can further strain internal cooperation and slow down joint economic and geopolitical objectives. Additionally, these tensions might diminish its ability to challenge the dominance of established powers like the G7.

In recent years, BRICS nations have been significantly affected by rising interest rates in advanced economies, particularly in the United States and the European Union, which have made investments in higher-risk markets such as those in the BRICS bloc less appealing. At the same time, global FDI trends are increasingly shifting towards high-tech, green energy, and service sectors, where G7 countries possess a clear comparative advantage. While BRICS countries have historically been key destinations for investment in commodities and manufacturing, they are adjusting at a slower pace to these emerging global investment trends.

Income inequality continues to pose a significant challenge across many BRICS nations. While these countries have experienced considerable economic growth and improvements in living standards for parts of their populations, large segments still face persistent poverty and inadequate access to basic services. According to the Gini coefficient, Brazil and South Africa consistently register some of the highest levels of income inequality globally, with values often exceeding 0.50. In contrast, China, India, and Russia report moderately lower Gini coefficients, generally around 0.35 (World Bank Data, 2024d). Nonetheless, these figures still reflect substantial disparities, often driven by urban–rural divides, uneven regional development, and, in Russia’s case, a notable concentration of wealth among top income earners. These persistent inequalities threaten to undermine social cohesion and hinder inclusive development across the BRICS bloc.

Addressing these challenges is critical for BRICS countries to fully realize their economic potential, strengthen their global position and become a strong competitor for the G7 countries. While these nations continue to work towards overcoming these hurdles, their ability to cooperate effectively and implement necessary reforms will be key to their future success.

7. Conclusion

The shifting balance of power from the G7 to BRICS carries significant geopolitical and economic implications for the global order. As BRICS countries—particularly China and India—continue to expand their economic influence, they are challenging the longstanding dominance of the G7 in shaping global economic policy, trade norms, and development agendas. The emergence of BRICS represents not merely an economic bloc, but a symbolic and operational challenge to Western-led governance structures (Cooper, 2016). This rebalancing reflects a broader transformation toward a multipolar world, where emerging economies assert greater agency in international institutions such as the United Nations, IMF, and World Bank.

Economically, the rise of BRICS contributes to the diversification of global growth engines. With their large populations, expanding middle classes, and increasing industrial capacities, BRICS economies offer alternative markets and sources of investment. This shift may lead to new trade alignments, south-south cooperation initiatives, and regional infrastructure projects—such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the New Development Bank—potentially reducing dependency on Western financial institutions. As of 2023, the BRICS bloc (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) accounted for approximately 33,2% of global GDP when measured by purchasing power parity (PPP), surpassing the G7's share of around 29% (World Bank Data, 2024e). The expanding economic footprint of BRICS signifies its growing influence in the global economy, positioning the bloc as a formidable counterpart to traditional Western economic alliances.

Politically, the growing influence of BRICS may challenge the normative frameworks traditionally promoted by G7 countries, including those related to democracy, human rights, and liberal economic policies. BRICS nations often advocate for a more state-centric and sovereignty-focused model of governance, which could alter the global discourse on issues such as development, climate policy, and digital regulation. Moreover, this power shift could increase competition and geopolitical tensions, particularly between the BRICS and G7 blocs. Issues like trade wars, sanctions, and diplomatic alignments are likely to become more complex. However, it also opens the door for more inclusive and balanced multilateral cooperation, where global governance structures evolve to better represent the diversity of the 21st-century international system. In sum, the rise of BRICS relative to the G7 signifies a profound transformation in global power dynamics, with far-reaching consequences for economics, governance, and international relations.

BRICS positions itself as a reimagined model of the global order—an alternative to the Western-dominated system. It emphasizes principles such as cooperation, mutual respect, and equilibrium of interests, in contrast to frameworks characterized by dominance, discrimination, or hierarchical power structures. Despite its collective identity, the BRICS grouping is characterized by substantial internal diversity in political regimes, economic models, and strategic priorities. This heterogeneity often generates intra-group tensions, as member states pursue distinct national agendas and vie for regional influence. Such divergences can impede the bloc’s ability to adopt cohesive positions on critical global issues, and as membership expands, these internal complexities may become more pronounced.

While BRICS is unlikely to surpass the G7 in overall economic terms in the near future—given the latter's higher levels of per capita income, technological advancement, and institutional development—it nevertheless represents a formidable competitor in the evolving global economic landscape. The sustained functioning of BRICS and its growing prominence in international affairs underscore the group's symbolic significance and increasing geopolitical relevance. BRICS has emerged as a notable actor in global governance, positioning itself as a counterweight to the traditional Western-led order and contributing to the evolution of a more multipolar international system. It is reasonable to anticipate that the BRICS phenomenon will continue to attract significant attention from scholars of international relations in the foreseeable future.

---

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

---

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The views, statements, opinions, data and information presented in all publications belong exclusively to the respective Author/s and Contributor/s, and not to Sprint Investify, the journal, and/or the editorial team. Hence, the publisher and editors disclaim responsibility for any harm and/or injury to individuals or property arising from the ideas, methodologies, propositions, instructions, or products mentioned in this content.

References

- Acharya A., 2020. The End of America Order, (2nd ed.). Polity Press. Chapter 1, pp. 4, 8, 10, [online] Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342345330_The_End_of_American_World_Order_Ch1, [Accessed on 8 September 2024].

- Basrur R., 2017. Modi’s foreign policy fundamentals: A trajectory unchanged. International Affairs 93(1) 7–26; DOI: 10.1093/ia/iiw006, [online] Available at: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/ia/INTA93_1_02_Basrur.pdf , [Accessed on 10 September 2024]

- BRICS, 2014a, Agreement on the New Development Bank. [online] Available at: http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/140715-bank.html , [Accessed on 12 September 2024]

- BRICS, 2014b, Treaty for the Establishment of a BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement. [online] Available at: http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/140715-treaty.html , [Accessed on 12 September 2024]

- Byrappa R., 2017. Comparing Immanuel Wallerstein’s critique of the BRICS with that of the creation of the United Nations. Dvacáté století, 9(2), 73–86, [online] Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20180410082409/https://sites.ff.cuni.cz/dvacatestoleti/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2018/02/Ramachandra_Byrappa_73-86.pdf , [Accessed on 8 September 2024].

- Cooper, A. F., 2016. The BRICS: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, [online] Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780198723394.001.0001, [Accessed on 3 September 2024].

- Cooper, A. F., and Stolte, C., 2019. Insider and Outsider Strategies of Influence: The BRICS’ Dualistic Approach Towards Informal Institutions. New Political Economy, 25(5), 703–714, [online] Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2019.1584167 [Accessed on 11 September 2024].

- European Commission, 2014. The Hague Declaration following the G7 meeting on 24 March. Press corner. [online] Available at: ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/de/STATEMENT_14_82 , [Accessed on 13 September 2024]

- European Council, 2024. G7 Leaders’ Communiqué - Borgo Egnazia, Italy. Press releases. [online] Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2024/06/14/g7-leaders-communique-borgo-egnazia-italy-13-15-june-2024/ , [Accessed on 13 September 2024]

- Hurrell, A., 2006. Hegemony, Liberalism and Global Order: What Space for Would-Be Great Powers? International Affairs, 82(1), 1–19, [online] Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227539418_Hegemony_Liberalism_and_Global_Order_What_Space_for_Would-Be_Great_Powers , [Accessed on 10 September 2024].

- IMF DataMapper, 2024. Real GDP Growth (Annual %). [online] Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/BRA/CAN/CHN/FRA/DEU/IND/ITA/JPN/GBR/USA/RUS/ZAF, [Accessed on 14 September 2024]

- O’Neill, J., 2001. Building Better Global Economic BRICs. Global Economics Paper No. 66, Goldman Sachs, pp. 1, [online] Available at: https://www.goldmansachs.com/pdfs/insights/archive/archive-pdfs/build-better-brics.pdf , [Accessed on 2 September 2024].

- Petropoulos, S., 2013. The emergence of the BRICS – implications for global governance. Journal of International and Global Studies, 4(2), Article 3. pp 48., [online] Available at: https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1145&context=jigs, [Accessed on 5 September 2024].

- Ranking Royals, 2024. Active Military Manpower by Country – Top 146 Countries. [online] Available at: https://rankingroyals.com/infographics/active-military-manpower-by-country-top-146-countries/, [Accessed on 15 September 2024]

- Stuenkel, O., 2015. The BRICS and the Future of Global Order. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books., Chapter 5, pp.77

- Transparency International, 2023, Corruption Perceptions Index 2023. [online] Available at: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2023 , [Accessed on 17 September 2024]

- UNCTAD, 2024. World Investment Report 2024, Annex table 01: FDI inflows, by region and economy, 1990-2023, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. [online] Available at: https://unctad.org/topic/investment/world-investment-report, [Accessed on 16 September 2024]

- Wallerstein, I., 2016. The BRICS – A Fable for Our Time. Fernand Braudel Center. [online] Available at: https://iwallerstein.com/the-brics-a-fable-for-our-time/ , [Accessed on 10 September 2024]

- World Bank Data, 2024a. GDP growth (annual %). [online] Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?end=2023&locations=CN-IN&start=2000 , [Accessed on 14 September 2024]

- World Bank Data, 2024b. Population, total. [online] Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL , [Accessed on 15 September 2024]

- World Bank Data, 2024c. Merchandise exports (current US$). [online] Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/TX.VAL.MRCH.CD.WT?most_recent_value_desc=true [Accessed on 16 September 2024]

- World Bank Data, 2024d. Gini index. [online] Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?most_recent_value_desc=true , [Accessed on 17 September 2024]

- World Bank Data, 2024e. GDP, PPP (current international $). [online] Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.PP.CD , [Accessed on 18 September 2024].

Article Rights and License

© 2024 The Author. Published by Sprint Investify. ISSN 2359-7712. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.