Keywordseconomic sanctions macroeconomic impact Russian Federation

JEL Classification F51, E66, O11

Full Article

1. Introduction

In 2014, the imposition of comprehensive economic sanctions on the Russian Federation by the United States, the European Union, and several other Western nations marked the beginning of a protracted period of international economic isolation. These sanctions, which were initially a response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea, have since been expanded and intensified, particularly following the geopolitical events of 2022. Targeting critical sectors such as energy, finance, defense, and technology, these measures have reshaped Russia’s economic landscape in profound ways. This article seeks to explore the macroeconomic impact of these sanctions over the past decade, analyzing both the immediate and long-term consequences on key economic indicators, including GDP growth, inflation, trade balances, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows and exchange rate volatility.

While sanctions are a common tool of international diplomacy, their long-term effects on large, resource-rich economies like Russia are complex and multifaceted. On one hand, sanctions have disrupted traditional trade relations, hindered foreign direct investment, and spurred inflationary pressures. On the other, Russia has demonstrated resilience through a combination of fiscal adjustments, import substitution policies, and the development of alternative trade partnerships, particularly with non-Western countries. This article examines how these adaptive strategies have shaped the Russian economy, with a focus on the challenges and opportunities presented by a decade of sanctions.

This paper investigates the extent to which sanctions have driven structural change in the Russian economy. It also evaluates the effectiveness of these measures as a geopolitical tool, considering both the immediate disruptions and the longer-term economic realignments that have occurred. Ultimately, the paper aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how sustained economic pressure has impacted Russia’s macroeconomic trajectory and its global economic positioning.

2. Literature Review

Economic sanctions have long been a tool of international policy, yet their efficacy, particularly in the context of large and resource-rich economies like Russia, remains a subject of intense debate. The literature on sanctions often examines their immediate effects on target economies—such as inflation, GDP contraction, and currency instability—but less attention has been paid to the long-term structural changes they induce. This section provides a review of the key theoretical frameworks and empirical studies that have addressed the impacts of sanctions on Russia’s economy, with a focus on both short- and long-term consequences.

The theoretical foundation of sanctions rests on the idea that economic pressure can force policy changes by diminishing a state’s economic well-being and increasing domestic political pressures. The sanctions imposed on Russia in 2014, coupled with a sharp drop in oil prices, put significant pressure on the ruble, causing inflation to surge, market instability, and concerns about financial stability. In its 2015 report, the IMF predicted that Russia would face a short-term recession, driven by a decline in domestic demand due to falling real wages, higher capital costs, and reduced confidence. The escalation of geopolitical tensions was identified as the primary risk to the economic outlook. (IMF, 2015). Viktorov and Abramov contend that these sanctions were relatively moderate, as Russia continued to have access to the international SWIFT payment system, foreign investors were not prohibited from purchasing Russian domestic sovereign debt securities, and no oil embargo was imposed on trade with Russia (Viktorov & Abramov, 2019).

In the years following the initial shocks, Russia began to adapt to the sanction regime. In his book, called `Russia’s Response to Sanctions: How Western Economic Statecraft Is Reshaping Political Economy in Russia`, Connolly supports the idea that sanctions initially caused disruption but their effects on targeted sectors quickly diminished due to Russian authorities' strategic response. He believes that Russia’s countermeasures, acted as a catalyst for structural change, a shift towards greater dependence on domestic resources (Russification) and the creation of a more diversified foreign economic strategy, with a growing emphasis on building stronger relations with non-Western nations (Connolly, 2018).

The sanctions imposed on Russia in 2022 were significantly more severe and comprehensive than those enacted in 2014. While the 2014 measures primarily targeted specific individuals, financial institutions, and certain sectors like defense and energy, they left major components of the Russian economy—such as access to the SWIFT payment system and oil exports—largely intact. In contrast, the 2022 sanctions, triggered by Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, included sweeping restrictions such as disconnecting major Russian banks from the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), freezing a large part of the Central Bank of Russia’s foreign-exchange reserves, imposing broad export controls on critical technologies, and enacting bans on Russian oil and gas imports by key Western economies. This new wave of sanctions reflected unprecedented international coordination and aimed to isolate Russia from global financial and trade systems to a far greater extent than in 2014.

Bali, Rapelanoro, and Pratson examine the indirect macroeconomic impacts of Western sanctions on Russia following its annexation of Crimea and involvement in Eastern Ukraine. Utilizing a structural vector autoregressive (SVAR) model with time-varying sanction indices, the authors move beyond traditional binary approaches to assess how sanctions influence key economic variables. Their findings reveal that sanctions affect Russia's GDP indirectly by impacting inflation, interest rates, and the exchange rate—a process they term the "sanction transmission mechanism (Bali et al, 2024).

There is a growing body of work that questions the overall effectiveness of sanctions as a tool of international policy. In his 1997 article "Why Economic Sanctions Do Not Work," political scientist Robert A. Pape argues that economic sanctions are largely ineffective as a tool of foreign policy. He contends that sanctions often fail because they do not impose sufficient pressure on the targeted regime to compel compliance, and they can inadvertently strengthen the resolve of the sanctioned government by rallying domestic support against external threats. Pape concludes that policymakers should be cautious in relying on sanctions and consider alternative strategies for achieving foreign policy objectives (Pape, 1997).

Daniel W. Drezner's 2011 essay, "Sanctions Sometimes Smart: Targeted Sanctions in Theory and Practice," critically examines the concept of "smart sanctions," which are designed to target specific individuals, entities, or sectors within a country to minimize broader humanitarian impacts. While these sanctions aim to address the shortcomings of comprehensive trade sanctions, Drezner argues that there is no consistent evidence demonstrating their effectiveness in achieving desired political outcomes (Drezner, 2011)

In Russia`s case, Gaddy and Ickes believe that sanctions ultimately strengthen Putin’s control over Russia’s economy and political landscape. They undermine the more independent and modern sectors of the Russian economy while consolidating Putin's power. Instead of weakening his leadership, sanctions serve to rally the public in support of him, diminishing the influence of liberal political forces in Russia. The authors argue that the current strategy of using sanctions and isolation will not only fail to halt Putin's actions in Ukraine but also hinder Russia's long-term development as a modern, globally integrated nation. This approach, they contend, makes it more difficult to achieve the broader goal of fostering a more democratic and open Russia (Gaddy & Ickes, 2014). Analyzing the impact of sanctions on Russia, Floudas also concludes that the effects on the Russian economy have been less severe than anticipated, and the structure has proven more robust than all initial forecasts predicted, the Central Bank of Russia playing a pivotal role in stabilising the economy (Floudas, 2023).

On the other hand, Anders Åslund argues that the Western sanctions imposed on Russia since 2014 have had a substantial effect on the country's economy. The most significant impact stemmed from financial sanctions, which restricted Russia's access to Western capital markets, resulting in a marked reduction in foreign debt and a decline in investment. In contrast, the economic impact on the West was minimal, with Russian countersanctions having limited effects on EU economies, and European exporters largely maintaining their market share in Russia. Nevertheless, the broader and more systemic consequence of these sanctions has been a growing economic divide between Russia and global markets. The sanctions have reinforced state control, empowered Kremlin-aligned elites, and led to capital flight, further isolating Russia from the global economy (Åslund, 2019).

The literature suggests a complex interplay between sanctions and economic resilience in Russia. While sanctions have undoubtedly led to short-term economic hardship, Russia has demonstrated a significant capacity for adaptation through structural changes in its economy. However, these adaptations have come at the cost of slower economic growth, technological stagnation, and increased political centralization. This literature review underscores the need for further empirical analysis to assess the full extent of sanctions’ impact, particularly with regard to their long-term effects on Russia’s macroeconomic performance and its global economic positioning.

3. Methodology

This article employs a mixed-methods research design to examine the macroeconomic impacts of sanctions imposed on Russia starting from 2014. It integrates qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) with quantitative macroeconomic data to deliver a comprehensive, multidimensional evaluation of the sanctions' effects over time.

The qualitative analysis draws on key policy documents, academic literature, and reports from institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), European Council, European Commission, Council of Europe and the Russian Government to trace changes in economic policy, institutional adaptations, and structural transformations within the Russian economy. Particular attention is given to Russia’s trade diversification strategies, including its growing economic ties with non-Western partners such as China, India, and members of the Eurasian Economic Union.

The quantitative component focuses on key macroeconomic indicators—GDP growth, inflation, trade balance, foreign direct investment (FDI), and exchange rate volatility—to assess the direct economic effects of sanctions. GDP growth serves as an overarching measure of economic performance, while inflation is used to capture immediate price effects and monetary instability. Trade and FDI indicators offer insights into the changing dynamics of Russia’s external economic relations, and exchange rate volatility illustrates the pressures on the ruble arising from financial restrictions.

Data are sourced from reputable institutions including the IMF, World Bank, Central Bank of Russia (CBR) and United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). A 10-year time-series analysis facilitates a comparative assessment of economic patterns before and after the two major sanction periods—2014 and 2022—enabling the identification of both short-term impacts and long-term structural trends.

By integrating qualitative insights with empirical macroeconomic data, the methodology aims to capture both the direct economic outcomes and the broader structural consequences of a decade of sanctions on Russia’s economic trajectory.

4. Sanction Measures Against Russia

Russia is currently the most sanctioned country in the world. According to the most recent data, Russia faces over 20,000 sanctions targeting individuals, entities, vessels, and aircraft. This number surpasses that of Iran, which has approximately 5,000 sanctions, and significantly exceeds the sanctions imposed on countries like Syria, North Korea, Belarus and Venezuela (Forbes Georgia, 2024).

The imposition of sanctions against Russia began in 2012 with the passage of the Magnitsky Act, which targeted a list of individuals implicated in the murder of Sergei Magnitsky (CONGRESS.GOV, 2012). This initial focus on individual sanctions expanded in 2014 following Russia's annexation of Crimea, leading to the imposition of economic sanctions, including restrictions on trade and cooperation in military and technological sectors.

Immediately following the annexation of Crimea, the G7 countries—Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States—collectively decided to suspend their participation in the G8. This decision was made in response to Russia’s actions, which were deemed inconsistent with the principles upheld by the group. The G7 members emphasized that meaningful dialogue within the G8 framework could not continue under the prevailing geopolitical circumstances. As a result, they announced that future meetings would proceed in the G7 format until such time as the international environment allowed for a constructive and principled engagement with Russia (European Commission, 2014). Also, as a direct response to Russia's actions in Ukraine and the illegal annexation of Crimea, on April 10, 2014, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) adopted a resolution suspending the voting rights of the Russian delegation, along with their rights to participate in the assembly’s governing bodies and election monitoring missions (Council of Europe, 2014).

By February 2022, Russia had faced approximately 2,700 sanctions. However, more than 80% of the current sanctions were enacted in response to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Sanctions have been levied by around 50 countries, predominantly led by the United States, European Union and Canada (Forbes Georgia, 2024).

On March 2, 2022, in coordination with the United States and the United Kingdom, the European Union agreed to exclude several key Russian financial institutions from the SWIFT system, the principal global platform for secure financial messaging. This measure, which came into effect on March 12, 2022, was intended to significantly hinder the ability of these banks to conduct rapid and efficient international financial transactions. Additional banks were subsequently added to the sanctions list in later rounds. On the same day, the European Union also adopted further restrictive measures, including a ban on investments in projects co-financed by the Russian Direct Investment Fund and a prohibition on the export of euro-denominated banknotes to Russia (European Comission, 2022a).

Following this decision, the United States, European Union, Canada, United Kingdom, Japan, and Australia revoked Russia’s "most-favoured-nation" (MFN) trade status—a designation that ensures equal trading rights, including low tariffs and minimal trade restrictions. In response, most of these countries opted to significantly raise tariffs on a wide range of Russian imports. However, the European Union chose a different approach by imposing targeted sanctions rather than adjusting tariff rates, implementing comprehensive bans on specific imports and exports—a strategy considered more immediate and impactful. This coordinated policy shift was designed to intensify economic pressure on Russia, curtail its access to key markets, and undermine its financial capacity to sustain military operations in Ukraine (European Comission, 2022b).

On March 16, 2022, following 26 years of membership, Russia was formally expelled from the Council of Europe, becoming the first state in the organization’s history to be removed (Council of Europe, 2022). As a result of this expulsion, Russia forfeited its participation in all institutional bodies of the Council, including the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) and the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR).

As of July 2024, up to 7,000 legal entities and 13,000 individuals were under sanction, which include measures such as travel bans, trade embargoes, cessation of investments, freezing of international reserves, prohibitions on the purchase of Russian government bonds, exclusion of Russian banks from SWIFT, and sanctions against Russian scientists, athletes, and artists (Forbes Georgia, 2024). This process remains ongoing, with the number of sanctions steadily increasing, aimed at weakening Russia's industrial and military capacities, reducing state revenues, and applying sustained economic pressure.

The table below highlights the main differences between the sanctions imposed on Russia from the annexation of Crimea in 2014 up to the period preceding Ukraine’s full-scale invasion, and those implemented following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Table 1: Comparison of sanctions imposed on Russia: 2014–2022 vs. post-2022 full-scale invasion

| Sanctions (2014–2022) | Sanctions (Post-2022) | |

| Triggering Event | Annexation of Crimea and intervention in Eastern Ukraine | Full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 |

| Scope | Sectoral and targeted sanctions (individuals, select entities) | Comprehensive, economy-wide sanctions with global reach |

| Financial Measures | Partial access restrictions to Western capital markets for select banks and companies | Exclusion of major banks from SWIFT, freezing of large Central Bank reserves |

| Energy Sector | Restrictions on offshore Arctic energy projects and technology exports | Bans and price caps on oil and gas exports, halt of new Western investments in energy |

| Export Controls | Limited to dual-use technologies and military-grade equipment | Broad export bans including semiconductors, aerospace components, and software |

| Trade Restrictions | Moderate trade limitations | Wide-scale bans on imports/exports including luxury goods, machinery, electronics, and more |

| Individual Sanctions | Focused on key political/military figures and some oligarchs | Drastic expansion—over 13,000 individuals and 7,000 entities sanctioned globally |

| Multilateral Coordination | Strong US-EU alignment, but limited broader participation | G7 unity + involvement of countries like Japan, South Korea, Switzerland |

| Institutional Impact | Moderate restructuring of financial sector and policy response | Structural decoupling from global finance, acceleration of ruble-focused settlements and trade pivot to Asia |

| Long-Term Consequences | Lower growth, capital flight, reduced FDI | Deepening economic isolation, contraction in high-tech sectors, strengthened state control over economy |

Source: (OECD, 2023), (U.S. Department of State, 2024), (European Council, 2024), (Brown, 2023)

5. Macroeconomic Impact of Economic Sanctions

In 2013, Russia was the 8th largest economy in the world by nominal GDP, measured in US dollars. By 2023, however, it had dropped to around 11th place, overtaken by India, Italy, and Canada. GDP dropt from 2.3 trillion US$ in 2013 to 1.3 trillion US$ in 2016, a 43.5% drop due to: currency fluctuations, economic sanctions and broader global economic shifts (World Bank Data, 2024a). According to IMF estimates, Russia’s GDP, measured in nominal US dollars, is expected to recover to its 2013 level only by 2029. This reflects the prolonged impact of sanctions, weak investment, demographic challenges, and limited economic diversification, which have slowed the country’s growth potential compared to the pace seen before 2014 (IMF, 2024a).

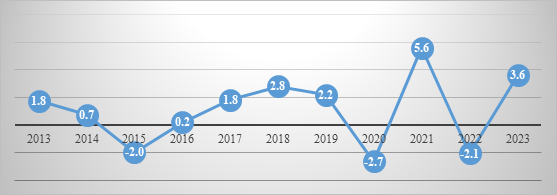

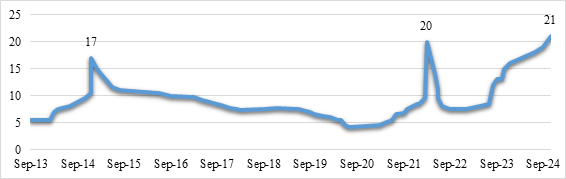

Figure 1: GDP growth (annual %) - Russian Federation, 2013-2023

Source: World Bank Data, 2024b

As we can see in Figure 1, in 2015, Russia entered a deep recession, triggered by a combination of falling global oil prices and Western sanctions imposed over the conflict in Ukraine. The main reason of this recession was the oil prices collapsed from over $100 per barrel in 2014 to below $40 by the end of 2015 (Yahoo Finance, 2024a). Since oil and gas made up about 50% of Russia’s federal budget revenues and around two-thirds of exports, the price crash was devastating. Sanctions, mostly financial (blocking major banks and companies from Western capital markets) and technology-related (especially energy sector tech), also caused damage. They made borrowing much harder and slowed long-term investment. However, in the short term, the sanctions' economic impact was smaller compared to the collapse in oil prices.

The ruble sharply depreciated, inflation soared above 15%, and consumer purchasing power fell significantly. Real GDP contracted by 2% in 2015. These shocks forced the government to implement austerity measures, tap into its reserve funds, and allow a partial floating of the ruble to stabilize the economy. Despite these efforts, investment and household consumption dropped, and economic uncertainty remained high throughout the year.

In 2020, Russia experienced a more significant economic downturn due to the combined effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and a collapse in global oil prices. The pandemic led to widespread lockdowns and a sharp decline in domestic and global demand, severely impacting sectors such as retail, manufacturing, and services. The pandemic-driven reduction in demand, combined with the oil price war stemming from Russia and Saudi Arabia’s disagreements over production cuts, led to a more than 50% drop in oil prices between January and May 2020. The economy contracted by 2.7% in 2020, marking its steepest recession since the 2009 global financial crisis (World Bank Data, 2024b).

Despite the alteady existing Western sanctions, in 2021 Russia’s economy rebounded, with GDP growth of 5,6%, driven by the recovery of global oil prices, the easing of pandemic restrictions, and higher demand for energy exports. The impact of sanctions on Russia’s economic growth remained relatively moderate until 2022, with fluctuations in oil and gas export prices exerting the most significant influence on GDP growth, reflecting the economy’s strong dependence on the energy sector.

However, after Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, the U.S., EU, UK, and other allies imposed unprecedented sanctions, that targeted Russian banks, trade and the energy sector (Tabel 1) and severily hit the Russian economy. These sanctions isolated Russia financially from the West, blocked investments, and created major logistics and supply chain problems, culminating in a GDP decline of 2.1% in 2022.

Russian consumers and businesses were hit by uncertainty, inflation, and job insecurity and big Western brands (like McDonald’s, IKEA, Nike, Inditex etc) pulled out of Russia, leading to loss of jobs and less consumer spending. In 2023, 546 companies halted Russian engagements or completely exit Russia, another 831 had curtailed their operations at least to some extent, while only 213 companies decided to continue business as usual (Yale School of Management, 2024). Energy companies, aviation and industrial firms, credit card providers, media outlets, management consultancies, tech giants, and banks are among the private sector actors that have exited the Russian market. Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, coupled with the deteriorating domestic business environment, has prompted numerous multinational corporations to reevaluate the scale of their operations in the country. The IMF's forecasts remain pessimistic, projecting that Russia’s GDP growth will decline, with annual growth rates not expected to exceed 1.2% between 2027 and 2030 (IMF, 2024b).

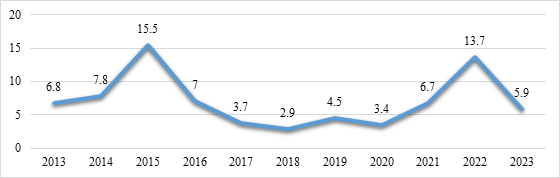

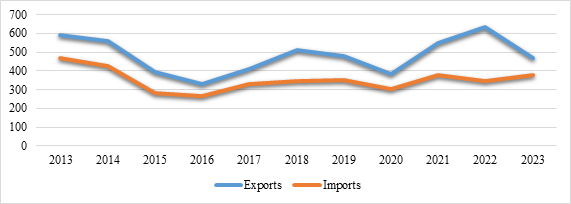

In the last 10 years, Russia experienced high inflation rates during two key period: 2015 and 2022 (Figure 2). The measures implemented by the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) have succeeded in stabilizing the economy following each shock; however, maintaining price stability remains a significant challenge that continues to place considerable pressure on the CBR.

Figure 2: Inflation rate, average consumer prices (annual %) - Russian Federation, 2013-2023

Source: IMF, 2024c

Analysing the 2014–2015 Russian financial crisis, Viktorov and Abramov describe the negative impact the fall in the oil prices had on the Russian ruble. They argue that the collapse in oil prices prompted speculative attacks against the currency. By the end of 2014, the ruble had depreciated by 58.2 percent against the U.S. dollar compared to its value in December 2013. The depreciation was especially severe in December 2014, when a steep drop in oil prices caused widespread panic in the domestic currency market, culminating in a dramatic collapse of the ruble's exchange rate against the dollar on December 16 (Viktorov & Abramov, 2019).

A secondary, though less influential, factor contributing to the ruble’s depreciation, at the end of 2014, was the imposition of Western sanctions, which restricted Russian banks and companies from accessing Western financing and technology. These measures undermined investor confidence in the Russian economy, prompting significant capital outflows. In response to the declining ruble and deteriorating economic conditions, businesses and individuals accelerated the transfer of their assets abroad to safeguard their wealth. This massive outflow of dollars and euros put even more downward pressure on the ruble.

A weaker ruble made imports much more expensive, driving up prices for goods like food, electronics, cars, and clothing, generating inflation. Prices also went up due to the sanctions imposed on Russia which restricted access to foreign goods and investments, causing supply shortages. In addition, in August 2014, the Russian government implemented countermeasures in the form of an embargo, targeting agricultural products, food, and raw materials from countries that had imposed sanctions on Russia, including the US, the EU, Canada, Australia, and Norway (The Russian Government, 2014). This created scarcity of basic food products (like cheese, fruits, vegetables, and meat), forcing prices higher. All these led inflation in 2015 to a maximum of 15.5, which caused the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) to react.

An initial measure undertaken by the Central Bank of Russia was the gradual increase of the key interest rate, which began in February 2014. However, in response to the sharp depreciation of the ruble and surging inflation, the CBR implemented a dramatic rate hike in December 2014, raising the key interest rate from 10.5% to 17% (Figure 3). The goal was to make borrowing more expensive, reduce consumer demand, and support the ruble by making it more attractive to hold Russian assets.

Figure 3: Key rate (%) - Russian Federation, 2013-2024

Source: Central Bank of Russia, 2024a

Another significant measure undertaken by the Central Bank of Russia in November 2015 was the decision to abandon its defense of the ruble and transition to a freely floating exchange rate regime. While this move carried the risk of exacerbating inflation in the short term, the Bank recognized that a floating ruble would better absorb external shocks, such as the decline in oil prices (Central Bank of Russia, 2016). Moreover, the shift allowed the CBR to conserve its foreign exchange reserves, which had been rapidly diminishing as previous interventions to stabilize the ruble had proved unsuccessful. Even after moving to a floating exchange rate, the CBR occasionally intervened by selling foreign currency to calm extreme volatility in the ruble market. These measures enabled the Central Bank of Russia to lower inflation and successfully achieve the annual inflation target of 4% in the following years.

A second significant increase in the inflation rate occurred in 2022, reaching 13.7% (Figure 2), largely as a result of the unprecedented sanctions imposed by the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. (Table 1). These sanctions targeted critical sectors such as finance, energy, defense, and technology. The resulting trade restrictions and financial isolation led to significant shortages of imported goods and services, thereby exerting upward pressure on prices. Within two weeks of the conflict’s outbreak, the ruble depreciated by 57% (Yahoo Finance, 2024c), substantially increasing the cost of imports and contributing to inflation across a broad spectrum of goods, including food, electronics, and pharmaceuticals. Additionally, as Western countries froze approximately half of the Central Bank of Russia’s foreign currency reserves—over $300 billion—it became exceedingly difficult for Russian authorities to stabilize the ruble through conventional interventions. Supply chain disruptions, exacerbated by sanctions, logistical challenges, and the withdrawal of numerous foreign firms, further strained the economy. More than 1,000 international companies curtailed or terminated operations in Russia (Yale School of Management, 2024), reducing market competition, limiting supply, and diminishing the availability of various goods and services, thereby intensifying inflationary pressures.

In response to the significant inflationary pressures following the onset of the Ukraine conflict and the imposition of Western sanctions in 2022, the Government and the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) implemented several measures to stabilize the economy and curb inflation. On February 28, 2022, in an effort to stabilize prices and the exchange rate, authorities mandated that exporters sell 80% of their foreign currency earnings. Concurrently, in response to rising borrowing costs, temporarily suspended the issuance of government securities and announced plans to reduce their volume throughout 2022 (The Russian Government, 2022).

Moreover, On February 28, 2022, the CBR raised its key interest rate from 9.5% to 20% to counteract the rapid depreciation of the ruble and rising inflation expectations (Central Bank of Russia, 2024a). This move aimed to support financial and price stability and protect citizens' savings from depreciation. As inflationary pressures began to ease and the ruble stabilized, the CBR initiated a series of rate cuts. By July 22, 2022, the key rate was reduced to 8%, reflecting a more favorable inflation outlook and subdued consumer demand (Figure 3).

Although inflation declined to 5.9% in 2023, price levels began to rise again in 2024. This resurgence in inflation was driven by multiple factors, notably the introduction of new coordinated sanctions by the European Union and the United States, which contributed to the depreciation of the ruble and increased the cost of imports. Additionally, escalating military expenditures, a surge in demand surpassing supply capacities, labor shortages, and rising wages—often transferred to consumers through higher prices—further intensified inflationary pressures. According to the Central Bank of Russia’s estimates, as of 21 October 2024, annual inflation stood at 8.4% and was projected to remain within the range of 8.0–8.5% by the end of the year. In an effort to steer inflation back toward the 4% target and to lower inflation expectations, the Central Bank of Russia resolved to further tighten its monetary policy. Consequently, on 25 October 2024, the Board of Directors of the CBR decided to raise the key interest rate by 200 basis points, setting it at 21.0% per annum. (Central Bank of Russia, 2024b). The IMF’s projections align with the long-term objectives outlined by the Central Bank of Russia, which anticipate that inflation will rise to 9.3% in 2025, before gradually declining and stabilizing around 4% during the period 2027–2030 (IMF, 2024c).

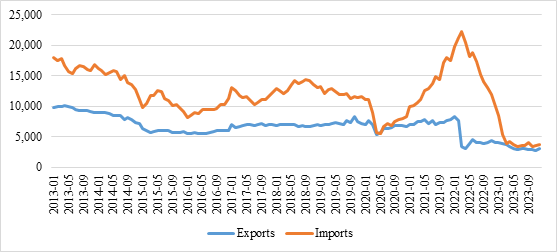

As illustrated in Figure 4, Russia’s exports and imports have experienced significant disruptions over the past 10 years due to a variety of factors. A notable downturn in exports occurred in the latter half of 2014, primarily driven by the sharp decline in global oil and natural gas prices (Yahoo Finance, 2024a, 2024b). Given that revenues from the oil and gas sector have long been a cornerstone of the Russian economy—accounting for 30% to 50% of federal budget revenues over the past decade (The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, 2024)—the collapse in energy prices had substantial macroeconomic repercussions. Furthermore, the oil and gas sector contributes, on average, around 20% to Russia’s GDP (Statista, 2024), although this figure fluctuates depending on international price dynamics and, more recently, the effects of Western sanctions imposed in response to the war in Ukraine, as well as Russia's efforts to reorient its energy exports toward alternative markets.

Another significant factor contributing to this trend was the imposition of Western sanctions, which limited Russia’s access to international financial markets, advanced technologies, and specific energy-related equipment. At the same time, the global economic slowdown in 2015, especially in Europe and China (key markets for Russia), reduced demand for Russian commodities (oil, gas, metals). Additionally, the depreciation of the ruble—while marginally enhancing the competitiveness of exports—had adverse effects that outweighed its benefits, including heightened inflationary pressures and increased capital outflows.

Figure 4: Exports and Imports of good and services (billion US$) - Russian Federation, 2013-2023

Source: World Bank Data, 2024c and World Bank Data, 2024d

Russia’s imports followed a similar downward trajectory as its exports. The countermeasures introduced by the Russian government in 2014—specifically the ban on food imports from the U.S., EU, Canada, Australia, and Norway (The Russian Government, 2014)—led to a substantial decline in import volumes. Furthermore, the sharp depreciation of the ruble significantly increased the cost of foreign goods, domestic inflation peaked to 15.5% in 2015 (IMF, 2024c), significantly reducing purchasing power and demand for imported goods. The Central Bank’s high interest rates (up to 17%) (Central Bank of Russia, 2024a) curbed consumption and investment, further decreasing import demand.

Between 2016 and 2019, Russia's exports and imports gradually increased, supported by the recovery in global oil prices, stabilization of the ruble, and a growing diversification of energy exports, particularly toward China. Following the sharp contraction in trade caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia's international trade rebounded strongly, surpassing pre-pandemic levels. The sharp rise in oil and gas prices during the global recovery significantly boosted export revenues, while the resumption of economic activity and a strong ruble enhanced domestic demand and improved the affordability of imported goods.

After the 2022 sanctions Russia experienced severe disruption in export destinations, but due to the high prices in the first part of the year, the revenues remained initially high. The G7, EU, and other allies imposed a price cap on Russian seaborne crude and petroleum products starting late 2022. Although Russia continued to export to countries such as China, India, and Türkiye, it was often compelled to offer significant discounts. So eventhough export volumes remained relatively high, the revenue per barrel dropped considerably. Moreover, although Russia tried to redirect exports eastward, infrastructure limitations (e.g. limited pipeline capacity to Asia) hindered full substitution.

Prior to the outbreak of the war, the European Union represented Russia’s primary energy export market. However, following the invasion of Ukraine, the EU significantly curtailed its imports of Russian oil, natural gas, coal, and various other commodities, thereby severing a critical stream of revenue for the Russian economy. As illustrated in the graph below, the EU's long-standing trade deficit with Russia reached a peak in March 2022, largely due to the elevated prices of energy products. This deficit was subsequently reduced to €0.1 billion by March 2023 and remained relatively stable throughout the remainder of the year, reaching €0.6 billion in December 2023 (Figure 5).

Figure 5: EU trade in goods with Russia (million euro), 2013-2023

Source: Eurostat Data, 2024

Imports of petroleum oil from Russia decreased from 28% of all petroleum oil extra-EU imports in the fourth quarter of 2021 to 3% by the fourth quarter of 2023. Russia's share in extra-EU imports of natural gas declined from 33% in the fourth quarter of 2021 to 13% in the same quarter of 2023. The EU’s largest petroleum oil suppliers and natural gas suppliers in the same quarter in 2023 in extra-EU imports became the United States and Norway (Eurostat, 2024).

Russia’s imports sharply declined in 2022 due to the withdrawal of over 1,000 Western companies—including key goods suppliers—the collapse of the ruble, the imposition of capital controls, and the widespread unavailability of Western products (Yale School of Management, 2024). However, beginning in 2023, imports began to recover as the Russian government implemented measures to promote domestic production and import substitution (The Russian Government, 2022). Additionally, Russia established alternative supply chains through third countries such as Kazakhstan and Türkiye to circumvent restrictions and increasingly replaced Western suppliers with Chinese partners.

Following the introduction of Western sanctions in 2014 and more intensively after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia significantly reoriented its trade relations toward BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), the other members of the Eurasian Economic Union and other non-Western partners. This strategic shift aimed to diversify Russia’s economic partnerships, decrease its reliance on Western markets, and cushion the economic repercussions of international sanctions. As a result, by 2023, Russia's primary export destinations were China ($129 billion), India ($66.1 billion), Turkey ($31 billion), Kazakhstan ($16.1 billion), and Brazil ($11.1 billion). On the import side, Russia's leading trade partners were China ($110 billion), Turkey ($10.8 billion), Germany ($9.84 billion), and Kazakhstan ($9.78 billion) (The Observatory of Economic Complexity, 2024).

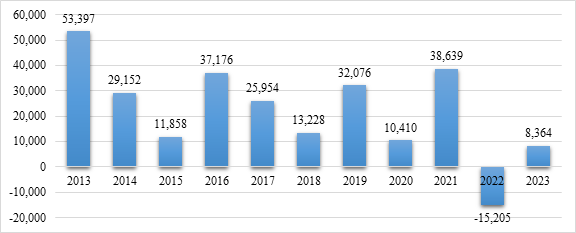

Sanctions imposed by Western countries following the annexation of Crimea in 2014 led to a decline in investor confidence, particularly in sectors such as finance, energy, and defense. However, the effect on FDI inflows remained moderate, as some investors continued operations due to Russia’s large market and natural resources. The situation changed dramatically in 2022 (Figure 6). The comprehensive and coordinated sanctions introduced by the United States, European Union, United Kingdom, and their allies in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine severely disrupted the investment climate.

Figure 6: FDI inflows (million US$) Russian Federation, 2013-2023

Source: UNCTAD, 2024

The outbreak of war and the subsequent imposition of international sanctions—such as asset freezes, export restrictions, and the removal of key Russian banks from the SWIFT system—have significantly heightened geopolitical and financial risk. This volatile environment generated widespread uncertainty among investors, prompting many multinational corporations to either suspend planned investments or completely withdraw from the Russian market. The atmosphere of elevated risk contributed to substantial capital flight, undermining the country’s investment climate.

A particularly notable consequence of this instability has been the large-scale withdrawal of foreign companies. According to the Yale School of Management (2024), more than 1,000 foreign firms either ceased or suspended their operations in Russia following the invasion of Ukraine. This mass exodus significantly curtailed both ongoing foreign direct investment (FDI) and the potential for future inflows, particularly from Western economies that had previously played a dominant role in Russia's investment landscape.

In response, the Russian government implemented a series of countermeasures aimed at stabilizing the economy and limiting capital outflows. These included capital controls and restrictions on the repatriation of profits by foreign firms. In 2022, authorities also introduced temporary bans on divestment by investors from “unfriendly” countries without prior government approval. While intended to prevent a disorderly exit of capital, such measures further eroded investor confidence by increasing uncertainty and complicating foreign firms’ withdrawal processes. The impact of these developments has been especially pronounced in sectors traditionally reliant on foreign investment, such as automotive manufacturing, retail, finance, and high-tech industries. These sectors either suffered directly from targeted sanctions or were weakened by the departure of international partners, technology providers, and capital inflows.

While Russia has attempted to mitigate the loss of Western capital by deepening economic ties with non-Western partners—particularly BRICS countries and Türkiye—the results have been limited. Although some new investment initiatives have emerged, they have fallen short of replacing Western FDI, primarily due to concerns about reputational damage and the threat of secondary sanctions. As a result, Russia's broader investment landscape remains constrained and vulnerable to external shocks. The sanctions regime post-2022 has caused a sharp decline in FDI inflows into Russia, with the country becoming increasingly isolated from global capital markets. The long-term implications include slower economic modernization, reduced access to advanced technologies, and increased reliance on state funding and domestic investment.

6. Conclusion

Although Russia has not suffered physical destruction of its productive assets as a direct consequence of the war, international sanctions have significantly constrained its trade capabilities—particularly its access to critical technologies and capital goods—while also deepening its isolation from the global financial system.

The initial wave of sanctions imposed on Russia between 2014 and early 2022—following the annexation of Crimea—had a relatively moderate impact on the Russian economy, especially when compared to the consequences of the simultaneous sharp decline in global oil prices. While the sanctions introduced during this period targeted individuals, certain state-owned enterprises, and sectors such as finance and defense, Russia was able to cushion much of the economic shock through its substantial foreign exchange reserves, a flexible exchange rate policy, and prudent fiscal management. Moreover, the Russian government implemented import substitution strategies and strengthened economic ties with non-Western countries, thereby mitigating some of the sanctions' immediate effects.

In contrast, the second wave of sanctions, triggered by Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, marked a turning point in terms of both scope and severity. These sanctions were far more comprehensive and coordinated, targeting not only key sectors like energy, banking, and technology, but also aiming to isolate Russia from the global financial system. Measures such as the freezing of central bank reserves, exclusion from the SWIFT payment system, withdrawal of over 1,000 multinational companies, and export controls on critical technologies significantly constrained Russia’s economic capabilities.

It is worth noting, however, that the Russian economy has not contracted to the extent that many international analysts and policymakers initially anticipated, despite being the most heavily sanctioned country in the world. At the onset of the conflict in Ukraine and the subsequent imposition of unprecedented sanctions by Western nations, a consensus among economists projected a prolonged and severe economic downturn. Many foresaw a scenario marked by a "lost decade," characterized by deep recession, capital flight, high inflation, and systemic financial instability.

While the sanctions did inflict significant disruptions—particularly in trade, technology imports, and foreign direct investment—their overall impact was mitigated by a combination of pre-emptive policy measures and rapid institutional responses. Chief among these was the strategic and decisive intervention of the Central Bank of Russia (CBR). These measures were complemented by a broader policy shift toward economic autarky, import substitution, and diversification of trade partnerships, particularly with countries outside the Western bloc. As a result, while the Russian economy did experience a contraction, it was far milder than the double-digit GDP decline that had been predicted by some Western observers. Adding to these factors is Russia’s vast territory and rich endowment of natural resources. Its substantial reserves of oil, gas, and raw materials have ensured a continuous flow of income and bolstered economic stability, helping to cushion the impact of external economic pressures.

The sanctions imposed on Russia have had, and continue to exert, a significant impact on its economy. Targeting key sectors such as finance, energy, defense, and technology, these measures have restricted access to international capital markets, hindered technological imports, and disrupted trade relationships with major Western economies. Although Russia has managed to implement short-term stabilizing measures and shift some of its economic ties toward non-Western partners, the long-term consequences—such as reduced productivity, technological stagnation, and declining foreign investment—pose serious challenges. The sustainability of Russia's current economic resilience remains uncertain, and it is yet to be seen whether the country can effectively adapt and maintain growth under prolonged sanctions pressure.

---

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

---

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The views, statements, opinions, data and information presented in all publications belong exclusively to the respective Author/s and Contributor/s, and not to Sprint Investify, the journal, and/or the editorial team. Hence, the publisher and editors disclaim responsibility for any harm and/or injury to individuals or property arising from the ideas, methodologies, propositions, instructions, or products mentioned in this content.

References

- Åslund, A., 2019. Western Economic Sanctions on Russia over Ukraine, 2014–2019. Peterson Institute for International Economics. [online] Available at: https://www.cesifo.org/DocDL/CESifo-Forum-2019-4-aslund-economic-sanctions-december.pdf, [Accessed on 18 October 2024].

- Bali, M., Rapelanoro, N. & Pratson, L.F., 2024. Sanctions Effects on Russia: A Possible Sanction Transmission Mechanism?. Eur J Crim Policy Res 30, 229–259. [online] Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-024-09578-w, [Accessed on 15 October 2024].

- Brown, C. P., 2023. Russia's War on Ukraine: A Sanctions Timeline. Peterson Institute for International Economics. [online] Available at: https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2022/russias-war-ukraine-sanctions-timeline, [Accessed on 24 October 2024].

- Central Bank of Russia, 2016. Monetary Policy Guidelines for 2017-2019. Moscow. [online] Available at: https://www.cbr.ru/content/document/file/48478/on_17-eng.pdf , [Accessed on 10 November 2024].

- Central Bank of Russia, 2024a. Interest Rates on the Bank of Russia operations. [online] Available at: https://www.cbr.ru/eng/oper_br/iro/#a_35859file, [Accessed on 10 November 2024].

- Central Bank of Russia, 2024b. Bank of Russia increases the key rate by 200 bp to 21.00% p.a.. Press release. Available at: https://www.cbr.ru/eng/press/pr/?file=25102024_133000Key_eng.htm, [Accessed on 21 November 2024].

- CONGRESS.GOV, 2012. S.1039 - Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012. [online] Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/senate-bill/1039, [Accessed on 20 October 2024].

- Connolly R., 2018. Russia’s Response to Sanctions: How Western Economic Statecraft Is Reshaping Political Economy in Russia. Cambridge University Press; 2018:1-8., [online] Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/russias-response-to-sanctions/introduction/F059F3C1F2440AED3060285153D1FCE6, [Accessed on 11 October 2024].

- Council of Europe, 2014. Parliamentary Assembly suspends voting rights of Russian delegation, excludes it from leading bodies. [online] Available at: https://www.coe.int/en/web/portal/-/parliamentary-assembly-suspends-voting-rights-of-russian-delegation-excludes-it-from-leading-bodies, [Accessed on 21 October 2024].

- Council of Europe, 2022. The Russian Federation is excluded from the Council of Europe. Newsroom. [online] Available at: https://www.coe.int/en/web/portal/-/the-russian-federation-is-excluded-from-the-council-of-europe, [Accessed on 22 October 2024].

- Drezner, D. W., 2011. Sanctions Sometimes Smart: Targeted Sanctions in Theory and Practice. International Studies Review, 13(1), 96–108. [online] Available at: https://academic.oup.com/isr/article-abstract/13/1/96/1807429?redirectedFrom=fulltext, [Accessed on 9 October 2024].

- European Comission, 2014. The Hague Declaration following the G7 meeting on 24 March. Press corner. [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_14_82, [Accessed on 21 October 2024].

- European Comission, 2022a. Ukraine: EU agrees to exclude key Russian banks from SWIFT. Press corner. [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_1484, [Accessed on 22 October 2024].

- European Comission, 2022b. Ukraine: EU agrees fourth package of restrictive measures against Russia. [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_1761 , [Accessed on 22 October 2024].

- European Council, 2024. Timeline - EU sanctions against Russia. EU sanctions against Russia, [online] Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions-against-russia/timeline-sanctions-against-russia/, [Accessed on 24 October 2024].

- Eurostat, 2024. Reduced levels of EU-Russia trade continue. [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20240222-2, [Accessed on 27 November 2024].

- Eurostat Data, 2024. EU27 (from 2020) trade by SITC product group. Geopolitical entity (partner): Russia. [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/EXT_ST_EU27_2020SITC__custom_16454141/default/table?lang=en, [Accessed on 28 November 2024].

- Floudas, D., 2023. Explaining the Limited Impact of Sanctions on Russia. Published in: The Dismal Scientist , Vol. XCI, No. Marshall Society: University of Cambridge (2023): pp. 4-9. [online] Available at: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/121346/, [Accessed on 17 October 2024].

- Forbes Georgia, 2024. The Most Sanctioned Countries. [online] Available at: https://forbes.ge/en/the-most-sanctioned-countries/, [Accessed on 23 October 2024].

- Gaddy C.G. & Ickes B.I., 2014. Can Sanctions Stop Putin?, Brookings Institution, [online] Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Can-Sanctions-Stop-Putin.pdf, [Accessed on 17 October 2024].

- IMF, 2015. Russian Federation. IMF Country Report No. 15/211, [online] Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2015/cr15211.pdf, [Accessed on 12 October 2024].

- IMF, 2024a. GDP, current prices (billions of U.S. dollars). [online] Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPD@WEO/RUS, [Accessed on 25 October 2024].

- IMF, 2024b. Real GDP growth (annual percent change). [online] Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/RUS?zoom=RUS&highlight=RUS, [Accessed on 1 November 2024].

- IMF, 2024c. Inflation rate, average consumer prices (annual %). [online] Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PCPIPCH@WEO/RUS, [Accessed on 8 November 2024].

- OECD, 2023. Assessing the Impact of Russia’s War against Ukraine on Eastern Partner Countries. OECD Publishing, Paris, [online] Available at: https://doi.org/10.1787/946a936c-en, [Accessed on 24 October 2024].

- Pape, R. A., 1997. Why Economic Sanctions Do Not Work. International Security, 22(2), 90–136. [online] Available at: https://doi.org/10.1162/isec.22.2.90, [Accessed on 8 October 2024].

- Statista, 2024. Share of the oil and gas industry in the gross domestic product (GDP) of Russia from 1st quarter 2017 to 2nd quarter 2024. [online] Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1322102/gdp-share-oil-gas-sector-russia/, [Accessed on 26 November 2024].

- The Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), 2024. Russia. Exports and Imports, [online] Available at: https://oec.world/en/profile/country/rus?selector400id=2, [Accessed on 29 November 2024].

- The Oxford Insitute for Energy Studies, 2024. Follow the Money: Understanding Russia’s oil and gas revenues. [online] Available at: https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Follow-the-Money-Russian-Oil.pdf, [Accessed on 26 November 2024].

- The Russian Government, 2014. On measures to implement the presidential executive order On Adopting Special Economic Measures to Provide for Security of the Russian Federation. [online] Available at: http://government.ru/en/docs/14195/, [Accessed on 12 November 2024].

- The Russian Government, 2022. Meeting with deputy prime ministers on current issues. Agenda: Additional measures to stabilise the financial and economic situation. [online] Available at: http://government.ru/en/news/44669/, [Accessed on 23 November 2024].

- UNCTAD, 2024. World Investment Report 2024, Annex table 01: FDI inflows, by region and economy, 1990-2023, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. [online] Available at: https://unctad.org/topic/investment/world-investment-report, [Accessed on 30 November 2024].

- U.S. Department of State, 2024. Ukraine and Russia Sanctions. Economic Sanctions Policy and Implementation. [online] Available at: https://www.state.gov/division-for-counter-threat-finance-and-sanctions/ukraine-and-russia-sanctions, [Accessed on 24 October 2024].

- Viktorov, I., & Abramov, A., 2019. The 2014–15 Financial Crisis in Russia and the Foundations of Weak Monetary Power Autonomy in the International Political Economy. New Political Economy, 25(4), 487–510. [online] Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2019.1613349, [Accessed on 10 October 2024].

- World Bank Data, 2024a. GDP (current US$). [online] Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?end=2023&start=1960, [Accessed on 25 October 2024].

- World Bank Data, 2024b. GDP growth (annual %) , [online] Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?end=2023&start=1961, [Accessed on 25 October 2024].

- World Bank Data, 2024c. Exports of goods and services (current US$), [online] Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.CD, [Accessed on 25 November 2024].

- World Bank Data, 2024d. Imports of goods and services (current US$), [online] Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.IMP.GNFS.CD, [Accessed on 25 November 2024].

- Yahoo Finance, 2024a. Brent Crude Oil. [online] Available at: https://finance.yahoo.com/quote/BZ=F/ , [Accessed on 26 October 2024].

- Yahoo Finance, 2024b. Natural Gas. [online] Available at: https://finance.yahoo.com/quote/NG=F/, [Accessed on 26 October 2024].

- Yahoo Finance, 2024c. USD/RUB (RUB=X). [online] Available at: https://finance.yahoo.com/quote/RUB%3DX/, [Accessed on 18 November 2024].

- Yale School of Management, 2024. Over 1,000 Companies Have Curtailed Operations in Russia—But Some Remain | Yale School of Management, [online] Available at: https://som.yale.edu/story/2022/over-1000-companies-have-curtailed-operations-russia-some-remain, [Accessed on 29 October 2024].

Article Rights and License

© 2024 The Author. Published by Sprint Investify. ISSN 2359-7712. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.